Blitzkrieg 101 revisited. One of my first post for the original Defensionem page (or Global Defence Journal as it was called back then) was “Blitzkrieg 101”. In that post, I briefly summed up Blitzkrieg in simple terms within a couple of lines. I know many books have been written on the subject and my intention is not to write another in-depth book. Frankly, I lack knowledge and time for this. But I want to go into the matter a bit deeper than I have previously done. This is still a short overview kept as simple as possible. Call it an introduction. call it “Blitzkrieg for noobs” if you like.

So. what is Blitzkrieg ? Well, it is manoeuvre warfare incorporating combined arms tactics. While the concept sounds pretty revolutionary for the 1930’s and 1940’s era, it is not. In fact, Blitzkrieg is simply an evolution of German military thinking going all the way back to 18th century Prussia ! They simply adapted older concepts to new technologies and new realities.

The main root of Blitzkrieg is the “Vernichtungsgedanke” or “concept of annihilation”. The concept dates all the way back to Frederick the Great. It relies on troop’s discipline and obedience and skilled officers displaying professional leadership to impose one’s will on the enemy and keep him unbalanced by moving units swiftly and fluidly on the battlefield, thus retaining the initiative.

Vernichtungsgedanke is tied to the similar concept of Vernichtungsschlacht . The Vernichtungsschlacht concept is a swift battle at tactical level that can change the whole strategic balance /situation by depriving the enemy of its main resources and forces: One major thrust bringing in a capital victory over the enemy, changing the whole military and political setup of the situation.

The famous 1914 Schlieffen Plan to attack and defeat France within 6 weeks by “wheeling” through Belgium was nothing less than an attempt at implementing the Vernichtungsschlacht concept: One big decisive battle relying on manoeuvre that could changer the strategic balance, defeat the enemy at operational level and force him to make concession or surrender.

The Schlieffen Plan failed for many reasons, but German inter-war military thinkers believed that Bewegungskrieg or manoeuvre warfare was still the way forward to win battles. The defeat of 1918 gave the Germans one advantage: They studied and pushed to find a solution and adapt their trusted tactics to the 20th century. People like Guderian and Von Seeckt, amongst others, worked hard on modernising the old doctrines and dusting off the old concepts. They also studied other people‘s work and never hesitated to embrace or include such concepts into their own. It is a well known fact that Guderian‘s views on the armour / manoeuvre warfare blend he was advocating was more than inspired by the work of the British Sir Basil Henry Liddell Hart and John Frederick Charles Fuller. It can also be said that Blitzkrieg copies elements of the Soviet Deep Battle Doctrine of the 1920‘s and 1930‘s.

Combining combined arms doctrine to the old battle of annihilation tactics and trusted but modernised manoeuvre warfare concept were some of the basis of Blitzkrieg. But not only.

You also need another old German military concept called “Auftragstaktik” ! Basically mission-type tactics. It is the combination of centralised intent with decentralized execution. In plain English, it is a 19th century German doctrine that relies once again on skilled professional leaders / officers. The high command gives its field commanders a precisely defined goal / mission, a time frame and deadline, resources and intelligence related to the mission. It is then up to the subordinates / field commanders to use their instincts and skills and display tactical flexibility to achieve said goal. The British and Americans would later on embrace the concept as “mission command”.

As you can see, relatively “junior” German officers were supposed to display tactical flexibility and make use of their own initiative, enjoying a far greater freedom of action than their Soviet, British or American counterparts. They were given an objective and how they achieved it was more or less (within reasons) up to them.

To achieve his mission in such circumstances, such a commander needed a thorough understanding of war and a world class curriculum in a military academy. He also needed natural leadership skills, an ability to read the battlefield and a good situational awareness. He was also expected to react instantly to any change in any given situation and improvise accordingly and autonomously. Such commander would basically have an instinct honed by years of learning and theory, shaped by practical experience. The Germans called this instinct “Fingerspitzengefühl” or finger tip feeling.

This, goes against the image we like to have of the Germans: Rigid disciplined people, almost robot like. The cliches and stereotypes are difficult to overcome, and yet, the Prussian and subsequently German military emphasised tactical flexibility, autonomous decision making and to a certain degree improvisation at relatively junior levels and this, since the 19th century !

Flexibility was not only present in the execution of a mission but in its planification as well as demonstrated by the “Kampfgruppen”: A Kampfgruppe is an ad-hoc combined arms formation assembled to fulfill one single defined mission. In effect, several units were bound together to create a formation that was perfectly suited to prosecute one single objective. It could be as small as a company and as big as a brigade and was assembled so as to be self sufficient and suited to the given task. It could have included anything from tanks, infantry, anti-tank guns, anti-aircraft guns and self propelled artillery to logistics and engineering units.

The Kampfgruppen gave the theatre commander great flexibility: A kampfgruppe was assembled for a specific mission and once the mission was over, all units could be sent back to their original outfit. A Kampfgruppe was usually named after its commander, but not always. While used mostly by the Wehrmarcht, the Kampfgruppe was sometimes used by the Kriegsmarine, too. The Kampfgruppe survives today in the form of the American style Task Force and British style Battlegroup.

The Kampfgruppe is also a great demonstration for the Combined Arms doctrine embraced by the Germans as early as in the 1930’s and which became an essential component to the Blitzkrieg. For this doctrine to work, you need a high degree of situational awareness and excellent communication. The Germans had radio sets everywhere and in everything. In an armoured outfit, every tank had a radio so that each individual tank commander could talk to other tank commanders, or directly to the field or group commander present at or near the front in his command vehicle. Said field or group commander was also in touch via different radio sets with artillery and aviation so that all resources could be coordinated at one point without delay. The concept went even further as the Luftwaffe deployed Fligerverbindungsoffiziere, or Flivos to field commanders and to the front lines. Those Flivos were in fact Liaison Officers or what we call today JTACs. They could upon request from the commander or of their own initiative call in air support or tactical bombing.

The way Germany integrated all the components of its armed forces together was not replicated by the main military/global superpowers up until much later and such integration and capabilities are still the envy of less developed armies up to this day.

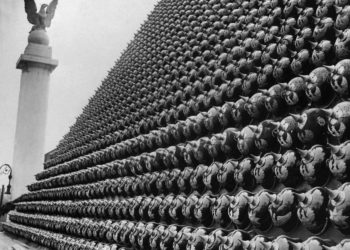

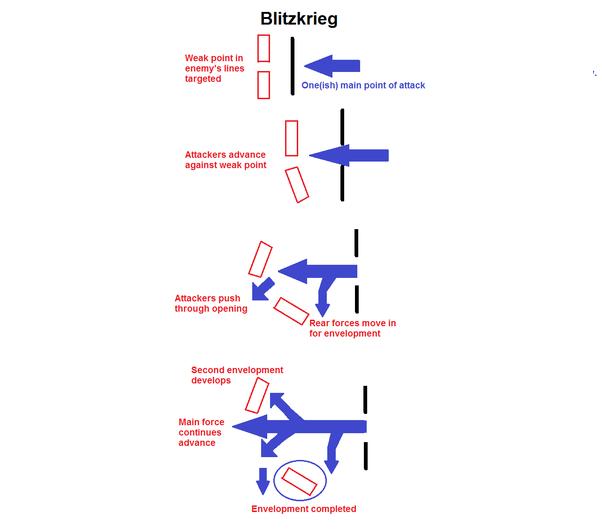

Blitzkrieg, then… Once the objective was defined and a battlegroup or army assembled, a weak spot had to be found in the enemy line by a combination of intelligence gathering and aggressive reconnaissance. That weak spot was to become the “Schwerpunkt” or center of gravity of the battle. The point where all forces must converge and concentrate to break through the enemy lines, where all efforts must focus. Interestingly, Carl von Clausewitz mentioned “Schwerpunkt” more than 40 times in his book “On War”. So once again, we see an older concept integrated into a more modern doctrine. The main thrust was expected to produce a breakthrough. Armour supported by infantry and artillery would focus on the enemy line’s weak point. Should the artillery be too far behind to support the tip of the spear (only 17% of the German armed forces at the time were motorised), the fire support could be provided by Stuka “flying artillery” dive bombers supplying CAS to the front line. All the while, tactical bombers would focus on the enemy rear lines, wreaking havoc, attacking enemy concentrations and assembly points, supply depots, lines of communication and so on. Following a breakthrough, the Germans would revert to another old battle concept of theirs called “Kesselschlacht” or “cauldrons battle(s)” / battle of encirclement(s).

Basically, the Germans would manoeuvre to encircle the enemy. One main frontal thrust would keep the enemy busy and unbalanced while elements on the flanks would execute a pincer movements and encircle the whole enemy force. Several Kesselschlacht or pockets / cauldrons could be created during that move, fragmenting enemy units in the process. The main thrust of the attack would then carry on deep into the enemy’s rear, racing toward its objective. Meanwhile each pocket would be reduced and destroyed by a combination of infantry, artillery, infantry support vehicles and aviation. The element of speed is very important here and the main force (armour) would bypass strongpoints during its race to the enemy’s rear. The strongpoints would then be de-facto cut off from their supply line and subsequently enveloped and surrounded by the following flanking/encircling force (infantry). As you can see, the Kesselschlacht is also a variation of the good old Vernichtungsgedanke or battle of annihilation concept.

So here you are. Blitzkrieg.