I remember the 1980’s well; and apart from the utterly dreadful pop music of that decade (my teenage years were the 60’s), the thing that always seemed to be with us was the interminable Iran-Iraq War.

It was regularly in the papers and the TV news; month after month; year in year out; but it wasn’t until years later, that I found we had only ever been told one side of it. We were fed the “Western” spin; and there was a fuller picture we weren’t shown.

The Shatt al-Arab was considered an important channel for both states’ oil exports, and control of it had been disputed for many years. In 1937, Iran and the newly independent Iraq signed a treaty to settle the dispute.

This treaty recognised the Iran-Iraq border to be along the low-water mark on the Shatt al-Arab’s eastern (Iranian) side, except at Abadan and Khorramshahr, where the frontier ran along the deep water line.

This gave Iraq control of most of the waterway and required Iran to pay tolls whenever its ships used it. One has to wonder what drove Reza Shah Pahlavi, who ruled Iran at that time, to sign such an obviously disadvantageous agreement.

In April 1969, Iran, now ruled by Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, abrogated the 1937 treaty and ceased paying tolls to Iraq when its ships used the waterway. The Shah justified his move by arguing, rightly, that almost all river borders around the world ran along the deep water, centre line, and by claiming that because most of the ships that used the waterway were Iranian, the 1937 treaty was unfair.

Iraq threatened war over the Iranian move, but when an Iranian tanker escorted by Iranian warships sailed down the river, Iraq, being the militarily weaker state, did nothing. But this assumption by Iran of the right to use the waterway toll-free rankled within Iraq.

In addition, Iraq had always laid claim to the Iranian province of Khūzestān, which they called Arabistan. It is an area populated by Arabs, as opposed to Persians, and of course, once it was found to be well laden with oil, the Iraqi claim became more pressing.

For some time Iraq had been encouraging an insurgency by the Iranian Arab inhabitants of the region. In the early 1970’s, in retaliation, the Shah began to encourage Iraq’s Kurdish rebels, giving them bases in Iran and arming them within Iraq.

From March 1974 to March 1975, Iran and Iraq had a few border scraps & squabbles; mainly over Iran’s support of Iraqi Kurds. In 1975, the Iraqis launched an ill-advised and rapidly defeated armoured incursion into Iran. Several other cross-border Iraqi attacks took place; however, Iran had the world’s fifth most powerful military at the time and easily defeated the Iraqis on each occasion.

In order to avoid further conflict, which they knew they would lose, Iraq decided to make concessions to Tehran in exchange for the Shah ending his support for the Iraqi Kurd rebellion.

The Algiers Agreement of 1975 was signed as a result. In it Iraq made territorial concessions in exchange for normalised relations. Iran agreed to end its support of Iraq’s Kurdish guerrillas and in return Iraq recognised that the entire frontier on the Shatt al-Arab waterway ran along the deep water line.

Saddam Hussain regarded the Algiers Agreement as a further humiliation, however, it did mean the end of Iranian (& US) support for the Peshmerga, who were then defeated by Iraq’s government in a short campaign that claimed 20,000 lives.

The British journalist Patrick Brogan wrote that “…the Iraqis celebrated their victory in their usual manner, by executing as many of the rebels as they could lay their hands on.”

The relationship between the Shah of Iran and Saddam Hussain thawed briefly in 1978, when Iranian agents in Iraq discovered plans for a pro-Soviet coup d’état against Iraq’s government, and Teheran passed the information on to Baghdad.

When informed of this, Saddam ordered the execution of dozens of his army’s officers and in a sign of reconciliation, expelled the then exiled Iranian Cleric Ruhollah Khomeini from Iraq.

Despite that, Saddam still considered the Algiers Agreement to be merely a truce, rather than a definite settlement and waited for the opportunity to ‘adjust’ it.

A further motive for the invasion was Saddam Hussein’s dream that Iraq could & should replace Iran as the dominant regional power in the Persian Gulf. Saddam believed that Iran, the regional power for so long, had been irredeemably weakened by its 1979 revolution, and that this allowed Iraq the opportunity to assume the role.

Before they invaded Iran, Iraq had a fully equipped and trained modern military, consisting of 200,000 men, 2,000 tanks, and 450 aircraft. The Iraqis could mobilise up to 12 mechanised divisions, and their morale was high. Throughout the 1970’s, Saddam had armed his forces with the latest and best military hardware that the Soviet Union would supply.

In Iran, on the other hand, things were a bit different. Following from their revolution, severe purges and shortages of spare parts for their US-made equipment had crippled the country’s military which, in 1978, had been considered so powerful.

Between February and September 1979, Iran’s Revolutionary Courts had executed 85 generals and forced all major-generals and most brigadier-generals into early retirement. The most highly skilled soldiers and aircrew were exiled, imprisoned, or executed. By September 1980, the government had purged 12,000 army officers.

When the invasion occurred, many pilots and officers were released from prison, or had their executions commuted, so as to be able to combat the Iraqis. The sanctions regime that they were living under meant that they had no new equipment, and very little chance to resupply. But, Iran still had at least 1,000 operational tanks, mainly British supplied Chieftains, & US M-60 & M-48 Pattons.

The only element of the Iranian armed forces that really concerned Iraq was the Iranian Air Force, which had several hundred operational aircraft, including F-4 Phantoms, F-5 Tigers & F-14 Tomcats. Due to sanctions, Iran was desperately short of spares for these US-supplied aircraft, but had already learned the art of cannibalising some to keep others operational.

In addition, a new paramilitary organisation had appeared in Iran, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), which was formed to protect the new regime and counterbalance the decaying army.

Despite having been trained purely as a paramilitary organisation, after the Iraqi invasion they were forced to act as regular troops. Initially, their commanders had refused to fight alongside the army, with some disastrous results, but, by 1982, they were successfully carrying out combined Army/IRGC operations.

Another paramilitary militia was founded in response to the invasion; the “Army of 20 Million;” commonly known as the Basij. The Basij, an old-fashioned “Citizen Army;” basically consisted of everyone else; everyone who could be persuaded to volunteer, and there were literally millions of them. The Iranians knew that they were fighting for their lives and the existence of their new Islamic Republic.

The Basij were poorly armed and had ‘soldiers’ as young as 9 and as old as 70. They were usually used in conjunction with the IRGC, being utilised as ‘human minefield clearance’ equipment and for ‘human wave’ attacks to seek out the weak points of heavily defended Iraqi positions.

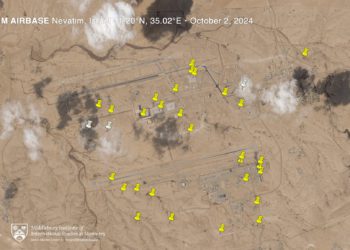

The pre-emptive Iraqi air-strikes, by Mig-21’s & 23’s, intended to decimate the Iranian Air Force, completely failed in their objective. They did achieve complete surprise, but were using bombs that proved to be inadequate against the hardened Iranian aircraft shelters.

As a result within hours Iran was able to go on the offensive, in the air at any rate; their Phantoms and Tigers concentrating on attacking Iraqi airfields and supply depots; their Tomcat interceptors escorting them and defending against Iraqi air force incursions.

Iraq’s blitz-like assaults against scattered, surprised and poorly-led Iranian forces led many observers to think that Baghdad would win the war within a matter of weeks. Indeed, Iraqi troops captured the Shatt al Arab and seized a forty to eighty kilometre wide strip of Iranian territory, along a wide front.

But, within weeks the Iraqi Air Force was crippled; forced to withdraw its remaining aircraft to the west of the country.

The Iraqi army logistics train was utterly destroyed, and the ground forces that had advanced so rapidly into Iran, recoiled into defensive positions and began to dig.

In addition, on 24th September the Iranian Navy attacked Basra, destroying two oil terminals near the Iraqi port of Faw, which seriously reduced Iraq’s ability to export oil.

On 30th September the IRIAF carried out Operation Scorch Sword. This was an airstrike on an almost-complete nuclear reactor about 10 miles from Baghdad. It was the first attack on a nuclear reactor in history; and the first on a nuclear reactor intended to prevent the development of a nuclear weapon. The attack actually wasn’t successful and only caused minor damage.

Perhaps surprisingly, it was the Israeli Air Force that finally destroyed the reactor, eight months later, on 7th June 1981.

Initially the Iraqi land forces made some gains in Khūzestān, but they were hard-won and their hopes of an Arab rising to greet them there were dashed. Iranian Arabs in Khūzestān remained loyal to the Iranian regime, and the Iraqi advances stalled.

But, after a month-long bloody battle, costing each side over 7,000 dead, the Iraqis did manage to take Khorramshahr.

Having temporarily obtained total air superiority, Iran was able to counter attack and in less than two years had recovered much of the territory briefly lost, and had begun to make inroads into Iraq itself.

In 1982 Iraq sued for peace, but that ceasefire was rejected by Iran, as the terms proposed would have meant Iraq remaining in possession of parts of Iran. Khomeini proclaimed that Iran would invade Iraq and would not stop until the Ba’ath regime was replaced by an Islamic republic or at least until Iraq withdrew from the disputed territories.

Around this time, during one cabinet meeting in Baghdad, the Iraqi Minister of Health, Riyadh Ibrahim Hussein, suggested that Saddam could perhaps step down temporarily as a way of easing Iran towards a ceasefire, and then afterwards return to power. Saddam asked if anyone else in the Cabinet agreed with the Health Minister’s suggestion.

When no one showed any support for this idea, Saddam escorted Riyadh Hussein to the next room, closed the door, drew his pistol and shot him. Saddam was still re-holstering his pistol as he returned to the meeting.

Later in 1982, the lack of parts for their aircraft drove Iran to end their air operations over Iraq, and use their air force purely for air defense and close air support.

In contrast Iraq, resupplied by both the USA and USSR, was able to resume their air offensive. The war on the ground descended into a remake of World War One; an entrenched war of attrition, with similar high casualty rates; masses of barbed-wire; trench raids; bayonet charges into machine gun fire; costly assaults against heavily fortified positions; the use of poison gas by Iraq on Iranian troops, civilians & Kurds; and human wave attacks by Iran. Meanwhile all major Iranian cities suffered Iraqi air raids and Scud missile attacks.

The next six years were characterised by highly costly assaults by both sides, resulting a situation of bloody stalemate; with very little movement by either side.

By the end of 1983, an estimated 120,000 Iranians and 60,000 Iraqis had been killed, but Iran had succeeded in removing the Iraqi forces from most of the Iranian territory they had occupied. Beginning in 1984, Baghdad’s military goal changed from controlling Iranian territory to denying Tehran any major gain inside Iraq.

Iraq attempted diplomacy; and in April 1984, Saddam Hussein proposed to meet Khomeini personally in a neutral location to discuss peace negotiations. Tehran rejected this offer and restated its refusal to negotiate with President Hussein.

Then came the “Tanker War;” with which Iraq sought to involve the superpowers as a means of ending the war. Baghdad believed this could be achieved by attacking Iranian shipping.

Early in 1984, Iraq purchased thirty Mirage F-1 fighters equipped with Exocet missiles from France and on 1st February launched a series of attacks on shipping, starting with the Iranian oil terminal and oil tankers at Kharg Island.

Saddam’s aim in attacking Iranian shipping was to provoke the Iranians to retaliate by closing the Strait of Hormuz to all maritime traffic, thereby bringing American intervention. The United States had threatened several times to intervene if the Strait of Hormuz were closed. As it happened, the Iranians limited their retaliatory attacks to Iraqi shipping, leaving the strait open to general passage.

Iraq declared that all ships going to or from Iranian ports in the northern zone of the Persian Gulf were now legitimate targets and would be subject to attack. In March 1984, an Iraqi Super Etendard fired an Exocet missile at a Greek tanker south of Khark Island. Until March, Iran had not intentionally attacked any civilian ships in the Gulf. But neutral merchant ships had become Iraq’s favourite targets, and the long-range Super-Etendards flew sorties farther south.

The new wave of Iraqi assaults, however, led Iran to reciprocate. In April 1984, Tehran launched its first attack against civilian commercial shipping by shelling an Indian freighter. Iran attacked a Kuwaiti oil tanker near Bahrain on 13th May and then a Saudi tanker in Saudi waters five days later, making it clear that if Iraq continued to interfere with Iran’s shipping, no Gulf state would be safe.

Seventy-one merchant ships were attacked by both sides in 1984 alone, compared with forty-eight in the first three years of the war. Lloyd’s of London estimated that the Tanker War damaged 546 commercial vessels and killed about 430 civilian sailors.

Most observers considered that Iraqi attacks, however, outnumbered Iranian assaults by three to one. Iran’s retaliatory attacks were largely ineffective because a limited number of aircraft equipped with long-range anti-ship missiles.

The Iranian Navy imposed a naval blockade of Iraq, using their British-built frigates to stop and inspect any ships thought to be trading with Iraq. They operated with virtual impunity, as Iraqi pilots had little training in attacking naval targets. Some Iranian warships attacked tankers with ship-to-ship missiles, while others used their radars to guide land-based anti-ship missiles to their targets.

Iran also used its new IRGC navy, which had Boghammar speedboats, fitted with rocket launchers, RPG’s, and heavy machine guns, to launch surprise attacks against tankers; and aircraft and  helicopters firing Maverick missiles and unguided rockets.

helicopters firing Maverick missiles and unguided rockets.

The Saudi decision in 1984 to shoot down an Iranian Phantom jet intruding over Saudi territorial waters played an important role in ending both belligerents’ attempts to internationalise the tanker war. Iraq and Iran accepted a 1984 UN-sponsored moratorium on the attacking of civilian targets.

Iraq began ignoring the moratorium soon after it went into effect and stepped up its air raids on tankers serving Iran and Iranian oil-exporting facilities in 1986 and 1987, even attacking vessels that belonged to the Arab states of the Persian Gulf.

Iran responded by escalating its attacks on shipping serving Arab ports in the Gulf.

But Iranian speedboat attacks on Kuwaiti shipping led Kuwait to formally petition foreign powers on 1st November 1986 to protect its shipping. The Soviet Union agreed to charter tankers starting in 1987, and the United States Navy offered to provide protection for foreign tankers reflagged as US, starting on the 7th March 1987 in its “Operation Earnest Will.”

Neutral tankers shipping to Iran were unsurprisingly not protected by Earnest Will, resulting in reduced foreign tanker traffic to Iran, since they risked Iraqi air attack.

By 1987 the Iranian air force was much weakened; possessing only 20 Phantoms, 20 Tigers, and 15 Tomcats in operational condition. At same time the Soviets began delivering more aircraft and weapons to Iraq. The main Iraqi air effort had shifted almost entirely against the Iranian economic infrastructure, primarily Persian Gulf oil fields, tankers, and the Kharg Island refinery.

On 17th May 1987, the USS Stark was hit by two Exocet missiles fired from an Iraqi Dassault Mirage F-1. The missiles were launched at about the time the plane was given a routine radio warning by the Stark. The frigate’s radar failed to detect the missiles, and a warning was given by the lookout only moments before they struck. Both missiles hit the ship, one exploding in the crews’ quarters, killing 37 sailors and wounding 21. Despite this, the USA, considering it a ‘friendly-fire’ accident, took no action against Iraq. Ironically, Washington used the Stark incident to blame Iran for escalating the war.

On 16th October 1987 an Iranian missile, launched from the Iranian-occupied Al-Faw Peninsula, hit and damaged a Kuwaiti oil tanker. In response, three days later, the US enacted “Operation Nimble Archer,” in which four US destroyers, USS Hoel, USS Leftwich, USS Kidd, and USS John Young bombarded two Iranian oil platforms that the IRGC were using to monitor ship movements. Later US troops landed on the damaged platforms and blew them up with demolition charges. Iran justifiably accused the US of militarily helping Iraq.

By late 1987, the Iraqi Air Force was counting on direct American support for conducting long-range operations against Iranian infrastructure targets and oil installations deep in the Persian Gulf. US Navy ships actively tracked and reported movements of Iranian shipping and aircraft. They supplied targeting information on several occasions in February and March 1988.

However when they failed to warn Iraqi aircraft of the presence of Iranian interceptors, the Iraqis suffered considerable losses.

In addition, at this time the US was running “Operation Prime Chance” alongside the aforementioned Operation Earnest Will. Prime Chance was a covert operation to search for and destroy Iranian vessels, including minelayers that were considered a threat to oil tankers carrying Iraq oil. This they did on several occasions. Prime Chance was proof enough for the Iranians to realise that now the US was actively assisting Iraq; not just with intelligence, targeting & logistics, but actively, militarily as well.

On 14th April 1988, the guided missile frigate USS Samuel B. Roberts struck a mine while deployed in the Persian Gulf as part of Operation Earnest Will. The ship was damaged, but didn’t sink and no lives were lost.

On 17th April 1988, Iraq launched Operation Ramadan Mubarak; a surprise attack against the 15,000 Iranian Basij troops on the al-Fawk peninsula.

On exactly the same day as this Iraqi attack, the United States Navy launched “Operation Praying Mantis” in retaliation against Iran for laying the mine that damaged the USS Samuel B. Roberts; destroying Iranian oil platforms, attack boats, patrol boats and frigates; with loss of hundreds of Iranian seamen. The USN action, in which they lost two helicopter crewmen, only ended when President Reagan thought that the Iranian navy had had enough.

(On 6 November 2003, the International Court of Justice ruled that “The actions of the United States of America against Iranian oil platforms on 19th October 1987 [Operation Nimble Archer] and 18 April 1988 [Operation Praying Mantis] cannot be justified as measures necessary to protect the essential security interests of the United States of America.”)

On 3rd July 1988, the cruiser USS Vincennes shot down Iran Air Flight 655, killing all 290 people on board. The American government falsely claimed that the USS Vincennes was in international waters at the time; that the civilian airliner had been mistaken for an Iranian Tomcat; and the USS Vincennes feared that it was under attack.

The Iranians maintained that the Vincennes was in Iranian waters, and that the passenger jet, an Airbus A300B2-203, was turning away and climbing; the normal flight pattern after take-off for its regular daily flight from Tehran to Dubai; and hard to mistake as a combat jet attacking.

U.S. Admiral William J. Crowe later admitted on US television that the USS Vincennes had been in Iranian territorial waters when it launched the missiles. He also accepted that Tomcats were never equipped with anti-ship missiles.

Reagan’s vice president, George H. W. Bush, defended the USS Vincennes actions, saying, “I will never apologise for the United States; Ever; I don’t care what the facts are.”

However, in 1996, the United States and Iran reached a settlement at the International Court of Justice which included the statement “…the United States recognised the aerial incident of 3rd July 1988 as a terrible human tragedy and expressed deep regret over the loss of lives caused by the incident…” As part of the settlement, the United States did not admit legal liability but agreed to pay on an ex gratia basis, $61.8 million, amounting to $213,103.45 per passenger, in compensation to the families of the Iranian victims.

Another aspect of this sanguinary throw-back to early 20th Century warfare, that is worth added consideration is the use of chemical weapons.

When considering the regular & indiscriminate use of these weapons was solely by Iraq; it’s also worth bearing in mind that, about 30 years later, when Iran’s ally Bashar al-Assad, allegedly used them once, unproven though that was; to the West, it was a vociferously condemned “Red Line” occurrence.

The first reported use of chemical weapons by Iraq occurred in November 1980.

Throughout the next few years, additional reports of chemical attacks circulated, and by November 1983, Iran began complaining to the UN that Iraq was using chemical weapons against its troops.

One of the most successful Iraqi chemical weapons tactics was the “two punch” attack. Using artillery, they would saturate the Iranian front line with rapidly dispersing cyanide and nerve gas, while longer-lasting mustard gas was launched via fighter-bombers and rockets against the Iranian rear, creating a “chemical wall” that blocked both reinforcement and retreat.

After Iran sent chemical weapons casualties to several Western nations for treatment, the UN dispatched a team of specialists to the area in 1984, again in 1986 and again in 1987; to verify the claims. The conclusion from all three trips was the same: Iraq was using chemical weapons against Iranian troops.

In addition, the second mission stressed that Iraq’s use of chemical weapons appeared to be increasing. The reports indicated that mustard gas and tabun nerve gas were the primary agents used and that they were generally delivered in bombs dropped by aircraft.

The third mission (the only one allowed to actually enter Iraq itself) also reported the use of artillery shells and chemical rockets and the use of chemical weapons against civilians.

On 21st March 1986, the United Nations Security Council made a declaration stating that; “Members are profoundly concerned by the unanimous conclusion of the specialists, that chemical weapons have been used by Iraqi forces against Iranian troops on many occasions, and the members of the Council strongly condemn this continued use of chemical weapons, in clear violation of the Geneva Protocol of 1925, which prohibits the use in war of chemical weapons.”

That had absolutely no effect.

On 28th June 1987, Iraqi fighter bombers attacked the Iranian town of Sardasht near the border, using mustard gas bombs. While many towns and cities had been bombed before, and troops attacked with gas, this was the first time that the Iraqis had attacked a civilian area with poison gas.

In March 1988, the Iranians carried out Operation Dawn 10. Though the Iranians advanced to within sight of their objective, Dukan, and captured around 4,000 Iraqi troops, the offensive was halted due to the Iraqi use of chemical warfare in the deadliest chemical weapons attack of the war. The Iraqi Republican Guard fired 700 chemical shells, while the other artillery divisions fired 200–300 chemical shells each, unleashing a poisonous cloud over the Iranian troops, killing or wounding 60% of them, as well as many of their prisoners.

In retaliation for the Iraqi-Kurds collaborating with the Iranians, Iraq launched a massive poison gas attack against Kurdish civilians in Halabja, recently captured by Iranian troops, killing some Iranian soldiers and thousands of Kurdish civilians.

Iran airlifted foreign journalists to the ruined city, and the images of the dead were shown throughout the world. However, the Western media’s mistrust of Iran and the collaboration by some, with Iraq, meant that some press reports blamed Iran for the attack.

At one point, media in the United States claimed that Iran had launched the attack and then tried to blame Iraq for it.

On 17th April, 25th May, 18th June and 25th June, 1988 Iraq launched massive air and artillery chemical weapons attacks on Iranian forces and border towns, using mainly mustard gas & the nerve agent Tabun.

In mid-1988, Saddam Hussein sent a warning to Khomeini, threatening to launch full-scale attacks on Iranian cities with weapons of mass destruction. Shortly afterwards, Iraqi aircraft bombed the Iranian town of Oshnavieh with poison gas, killing over 2,000 civilians.

The fear of an all out chemical attack against Iran’s largely unprotected civilian population loomed large with the Iranian leadership, and they realised that the international community had not the least intention of restraining or censuring Iraq.

In July 1988, Iraqi aircraft dropped cyanide bombs on the Iranian Kurdish village of Zardan. Dozens of other villages, and some larger towns, such as Marivan, were attacked with poison gas, resulting in even heavier civilian casualties.

And all this was at about time that the USS Vincennes shot down Iran Air Flight 655.

The marked lack of international sympathy disturbed the Iranian leadership, and they came to the justifiable conclusion that the United States was but one step away from openly waging a full-scale war against them; that Iraq was on the verge of unleashing its entire chemical arsenal upon their major cities and that the rest of the world just didn’t care.

It was in these circumstances that Iran eventually agreed to the UN brokered ceasefire. UNSC Resolution 598 became effective on 8th August 1988, officially ending all combat operations between the two countries.

In a recently declassified 1991 report, the CIA estimated that Iranian troops had suffered more than 50,000 casualties from Iraq’s use of chemical weapons. That official CIA estimate did not include the civilians killed. Current estimates are more than 200,000 died and that figure is rising as victims continue to succumb to the long-term effects. As of 2002, 5,000 of the 80,000 affected survivors receive regular medical treatment, while another 1,000 are hospital inpatients.

The chemical weapons Iraq used included H-series blister and G-series nerve agents.

Iraq built the agents into various offensive munitions including rockets, artillery shells, aerial bombs, and warheads on the Al Hussein Scud missile variant. During the war, Iraqi fighter-attack aircraft dropped mustard-filled and tabun-filled 250 kilogram bombs and mustard-filled 500 kilogram bombs on Iranian targets.

Iraq also installed spray tanks on a number of helicopters, for “crop-spraying” unprotected villages, and dropped 55-gallon drums filled with mustard gas, from low flying transport aircraft.

It is worth noting that despite being on the receiving end of regular & indiscriminate chemical weapons attacks, for 6 years; at no time did Iran retaliate in kind. This was mainly because the Ayatollah Khomeini considered that, “…the manufacture, stockpiling and use of all weapons of mass destruction to be Un Islamic”, and had issued a fatwa to that effect.

It should be remembered that the current Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, who spent time in the trenches during this war, has restated that fatwa, and confirmed that it relates to all weapons of mass destruction; including nuclear weapons.

According to Iraqi documents, materials for the manufacture and assistance in the development of chemical weapons came from firms in many countries; including the United States, West Germany, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and France.

Declassified CIA documents show that the United States was providing reconnaissance and targeting intelligence to Iraq around 1987/88, which was then used to launch chemical weapon attacks on Iranian troops and that the CIA were fully aware that chemical weapons would be deployed.

On 9th December 1991, Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, then UN Secretary General, reported that Iraq’s initiation of the war was unjustified, as was its occupation of Iranian territory and use of chemical weapons against civilians: “That Iraq’s explanations do not appear sufficient or acceptable to the international community is a fact.

“The attack cannot be justified under the charter of the United Nations, any recognised rules and principles of international law, or any principles of international morality, and entails the responsibility for conflict.

“Even if before the outbreak of the conflict there had been some encroachment by Iran on Iraqi territory, such encroachment did not justify Iraq’s aggression against Iran, which was followed by Iraq’s continuous occupation of Iranian territory during the conflict, in violation of the prohibition of the use of force, which is regarded as one of the rules of jus cogens.

“On one occasion I had to note with deep regret the experts’ conclusion that chemical weapons had been used against Iranian civilians in an area adjacent to an urban centre lacking any protection against that kind of attack.”

He also stated that had the UN accepted these facts earlier, the war would have almost certainly not lasted as long as it did. Iran, encouraged by the announcement, sought reparations from Iraq, but never received any.

The U.S. single-handedly blocked further UN-condemnation of Iraq’s use of chemical weapons. Consequently, Iraq was never sanctioned by the international community for its actions.

Most historians and analysts consider the war to have ended in stalemate. Certainly with help from both Super-Powers, and chemical weapons, Iraq could claim the military victory. Their losses (105,000–200,000) though horrendous, were much fewer than Iran’s (over 500,000.) They denied Iran any major territorial ambitions they may have had and persuaded Iran to accept the ceasefire.

But Iran did manage to gain their political goals of driving Iraq entirely from their territory; they thwarted Iraq’s major territorial ambitions in Iran, and, 2 years after the war had ended, Iraq permanently gave up all its claims to the Shatt al-Arab as well.