These extraordinary results of the OKH (Oberkommando das Heeres, the High Command of the German Army), the rapid advance and the large number of Soviet prisoners, followed by a sudden stop of the offensive at the gates of Moscow and the subsequent movement of the initiative towards the Soviets during winter led to birth of myths and controversies surrounding the German offensive in the East. Out of the rumors circulating after the war – or sometimes even during the war – how many are real and how many are just disinformation based on propaganda, deception or simply lack of knowledge?

On December 18th, 1940, Hitler issues ‘Führer Directive 21’. Through this, he orders the beginning of preparations for the invasion of the Soviet Union in a swift campaign, even before knocking Britain out of the war. For this, the OKH is to be split into two groups, to the North and South of the Pripet Marshes. Army Group North would advance on Leningrad, while Army Group South would aim for Donetsk. The main objective was the quick encirclement and destruction of the Soviet armies, to ruin the USSR’s capacity to wage war. Luftwaffe would annihilate soviet air force and support the ground operations, while the navy would protect Germany’s coastline and prevent Soviet ships from leaving the Baltic.

But even before that, in august 1940, the German Army had imagined a plan for striking the Soviet Union. Under the command of general Marcks, this invasion plan focused on Moscow and Kiev, using two army groups. Later in December, under general Halder, a new plan was created. This focused on Leningrad as the main target and also added a third Army Group Center. The final version, dictated through Directive No. 21, prioritized the encirclement and destruction of Soviet armies and the capture of Leningrad, while Moscow was seen as a secondary target.

Offensive preparations were to be completed by May 15, 1941. However, the assault has started on June 22nd, since units weren’t deployed on time. As time was essential for covering the lands of such a vast country, starting on June 22nd did have an impact on the outcome of the Operation, as days became shorter and autumn was getting ever closer, with rains that turned roads into mud.

But why was invasion postponed? And providing the Germans launched Operation Barbarossa earlier, as initially planned, could they have had any chances of success? It is often stated that the invasion of Greece in spring 1941 led to the delay of Operation Barbarossa. However, this doesn’t appear true if we look inside the OKH at the time. Operation Barbarossa and the invasion of Greece were planned concomitantly, which means the High Command knew exactly how many resources would be needed and therefore didn’t divert units from the East towards the Southern Front. The only real impact the invasion of Greece had on Operation Barbarossa was related to reinforcements, as the surplus of tanks situated in Greece took longer to be transferred to the Russian Front because of the heavy usage and needs of reequipment for the new theatre.

What caused the delay if it wasn’t the invasion of Greece? German logistics, which means troop mobilization and equipment deployment took longer than was planned on paper. Poor German logistics would become the ultimate reason in the failure of Operation Barbarossa. However, providing troops were brought to the Soviet border on time, would an invasion in spring 1941 be viable? Not so much, as that spring was extremely humid. This means that German troops would meet mud in which they’d sink knee deep along with all of their equipment, eventually leading to a gradual halt in operations and a slow advance. As flawed as June 22nd turned out to be, it looks like the only real date at which the Germans could have launched their operation that year.

Did the Soviet High Command (STAVKA) know about the upcoming invasion? Fortunately for the Germans, the Soviets were not aware of when the attack will take place, despite knowing it would happen at some point. Thus, the surprise effect was used to maximum advantage. Also, they were unaware of the objectives of the operations. Stalin believed the German attack would focus on the rich fields in the south, with its vast agricultural resources. This is why most of the Red Army was centered around Kiev and why the Wehrmacht advanced so slowly with the Southern Army Group, whereas the other two advanced relatively quick. The Soviets noticed a growth of military effectives on the German-Soviet border and expected an attack, but they could not estimate the exact date.

To this uncertainty contributed the german espionage network, which ‘intoxicated’ the Soviet commanders. They launched an ambitious plan in which trains full of ammunition and soldiers left the border and headed west during the day, only to turn back at night. Fake dispatches were issued and even radio stationed aired flawed information and orders. Therefore, up to the last minute, the date of the German offensive remained uncertain. Contrary to popular myths, Stalin did not know the date at which Operation Barbarossa would be launched.

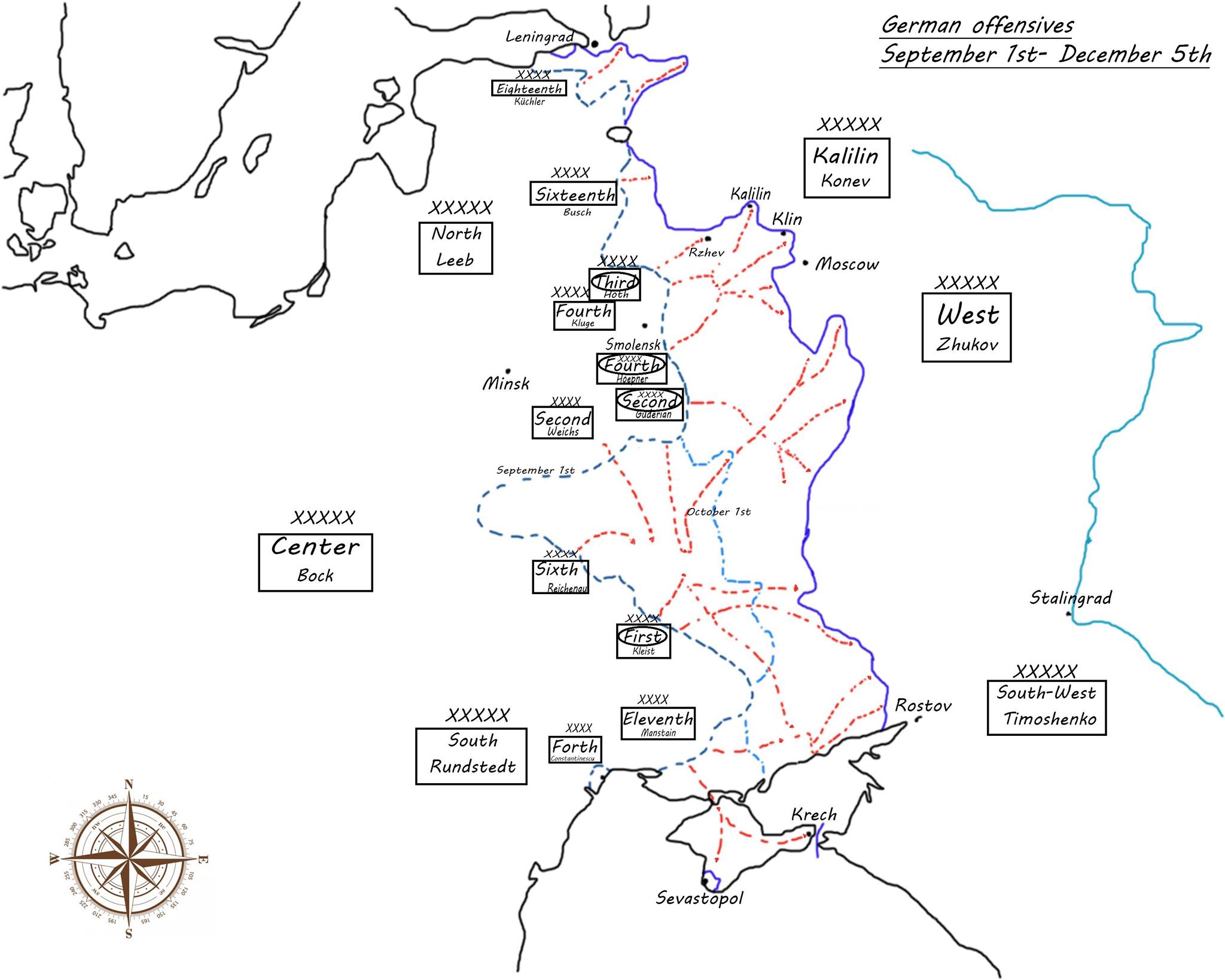

On the morning of June 22nd, the Wehrmacht, with approximately 3.8 million men, 3.400 tanks, 3.000 aircraft and 7.000 artillery pieces, invaded the Soviet Union. Surprised, the Red Army was quickly encircled and annihilated. Using their ‘lightning’ tactics, the Germans advanced fast and caught Soviet armies in ‘pockets’. This disaster was also the fault of bad communication between Soviet commanders and soldiers, as well as the lack of a proper supply network. Soviet reaction was delayed by the few radios they had, thus many units couldn’t even receive orders before being captured. Most of the Red Army was places south, around Minsk and Sevastopol, making a German advance in the north easy. On July 10th, Army Group North, under the command of von Leeb, reaches the Luga river, about 100km from Leningrad. Meanwhile, Army Group South, under the command of von Rundstedt, moves on with caution. Only on September 26th is Kiev encircled and 665.000 Soviet soldiers captured.

In the air, the situation seemed favorable to the Russians. 3.000 German planes met 8.000 Soviet planes, but many of them were obsolete and therefore ineffective in aerial warfare. Also, around 1.200 planes were destroyed in the first day, most of them while still grounded. Considering all these factors, the ratio between German and Soviet air forces seems more balanced.

At the beginning of July, most of the units belonging to the soviet Western Front were surrounded at Smolensk. However, in his struggle to ever move eastwards, Guderian allowed an important part of the Soviet forces to get out of the encirclement. At about 300km from Moscow, he was ordered to halt and turn around to close the pocket. Nearly 300.000 soldiers were captured, along with 3.200 tanks and 3.100 guns. But Army Group Centre was exhausted by combat and needed a break. On July 19th, Hitler issued Directive No. 33, transferring priority on the flanks to destroy Soviet forces near Kiev and Leningrad. Thus, Army Group Centre was further weakened, sending its forces to the north and south. It was then ordered to get into defensive while Guderian would make junction with Army Group South to encircle Kiev. This decision if often portrayed as the one which doomed Operation Barbarossa. However, Soviet armies on the flank of Army Group Centre were still a very real threat to the German supply lines and were even able to cut off the Army Group completely. The decision to clear the flanks first was justified, as an assault on Moscow would have exposed a big chunk of the Wehrmacht.

As summer was coming to an end, the German offensive seemed to be going very well in every sector of the front apart from Army Group North, which was unable to secure Leningrad. However most of the agricultural land and mines were under German control, while a big part of the Red Army was destroyed. At this point, Hitler didn’t see Moscow as an important objective, aiming to conquer it in spring of 1942. But some of his generals, including von Bock, Guderian and Hoth, argued that the Soviet army is weak and Moscow could be conquered fairly easy. This assumption was wrong and Operation Barbarossa was a doomed operation already. Although the Soviet army lost 5 million men, it was not broken completely. The main objective of the operation was not accomplished and the Wehrmacht was exhausted by continuous fighting in which it had lost half a million men. Above all this, with each passing day the Germans stretched their supply lines ever thinner, a problem which was already beginning to show.

On September 30th, after the Kiev pocket was ‘cleared’, the Germans launch Operation Typhoon, an attempt to conquer Moscow before the coming of winter. Pushing on with their encirclement tactics, they gained land and surrounded Soviet units near Viazma, then captured Mojaisk, about 100km from Moscow.

On September 19th, a curfew was decreed in Moscow. Following the battles of Kalinin and Kaluga, the Soviet capital was threatened with encirclement. Soldiers fought bravely against the Wehrmacht and did all they could to prevent the fall of the city. A common myth suggests that Siberian infantry saved Moscow during those desperate days. At a closer look, however, we notice that in December 1941, only three siberian divisions were present on the Western Front, way too few to change the course of the battle, many other reserves doing their job and fighting just as good.

The Wehrmacht reached 30km from Moscow, reports indicating that further observation units could even see the Kremlin through their binoculars. But even though the Germans were so close to victory, the offensive was called off. Lack of supplies meant tanks and infantry could not go any further. Months of exhausting fighting were starting to show. It was time for the soldiers to dig in for winter and prepare for the Soviet counter attack, which came on December 5th, pushing the Wehrmacht back about 100-200km.

It is rumored that Hitler refused to send winter clothes to the soldiers on the frontline because in his madness he still believed the offensive would be over with the coming of winter. However, it turns out this is not true. Hitler did issue an order to equip the troops on the frontline with clothes, but because of the bad roads and different track gauge, transport was difficult. German logistics suffered terribly and they had to prioritize fuel and ammunition to winter clothing. Thus coats came in small quantities compared to ammo and fuel, which were vital to carrying out an offensive.

How big of a factor was weather during those last days of Operation Barbarossa? During the offensive, only several episodes of bad weather were recorded and that only affected the Germans locally. Mud was a big issue for logistics and it did cause small delays, but with the coming of frost roads solidified again. As for the cold weather, there are no reports of illnesses until after Operation Typhoon was over due to lack of supplies. Low temperatures did not stop the Wehrmacht from conquering Moscow, but it definitely helped the Soviets in their Winter Counter-offensive.

Operation Barbarossa was doomed from the very start. Poorly planned and executed, it lacked proper objectives and was plagued by poor logistics. Even so, the decision seemed rational at the time, with the Soviets losing many soldiers against Finland a year prior and the USSR not being the super-power we now know it became after the war. It can be said that the failure of the German invasion in the East was the result of overconfidence in their own strength and not in underestimating the Soviets.

Bibliography:

- Moscow 1941: Hitler’s first defeat , Robert Forczyk

- The Storm of War: A New History of the Second World War, Andre Roberts

- The Second World War, The Eastern Front 1941-1945, Geoffrey Jukes, D.M. Horner

- Stratagèmes: Duperie, tromperie, intoxication, illusion pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Jean Deuve