War with China: Part III

Strategic Variables, Factors, Constraints and Influences

In the event of conflict with the PRC, there will be significant political and economical factors that come into play and influence the outcome of the conflict. These factors must be considered prior to any operation, and limitations originating from these factors are henceforth known as “Constraints”.

With the PRC, there are several constraints that will likely influence how they employ their military forces. Considerations over potential loss of trade with regional trading partners, potential loss of access to Western markets, humiliation of potential defeat, as well as nuclear war that threatens the mainland, are all considerations that the PRC will consider prior to engaging in armed conflict with the United States. If the PRC is determined to engage in war, it is likely that the PRC will not initiate a nuclear attack on the United States or its allies. It is possible that the PRC may initiate an attack directly on US forces forward stationed in Japan, Hawaii, and Guam if senior PRC decision makers conclude that doing so is more favorable than not.

The PRC will also initially seek to limit attacking potential non-aligned nations in order to avoid being seen as the aggressor on the global stage as well as trying to avoid the creation of additional belligerent participants in any future conflict. Prior to any conflict actually occurring, the PRC may attempt to leverage economic and diplomatic relations with regional nations that have ties to both China and the US. It would be the intent of the PRC to deny US forces access to the region in order to diminish offensive and defensive capabilities of US forces forward deployed, politically or militarily. If the PRC can accomplish this without direct military confrontation, then that will be seen as a strategic win for the PRC prior to the onset of hostilities.

The PRC would likely also leverage international laws, relations, and the lack of official recognition of the ROC as well as claim that the actions of the PRC are exclusively an internal matter. Since the West and most of the world does not recognize Taiwan as an independent nation, the PRC may likely attempt to utilize this approach prior to commencement.

US Response and Potential Constraints

The PRC has likely already focused on the exact language found in the 1979 Taiwan Relations Act (TRA). This also may likely influence PRC decisions to not attack 3rd party forces first before attempting to retake Taiwan. The critical factor in the amended version of the 1979 TRA is that it no longer requires the US to actually defend Taiwan, but instead merely spells out the US commitment to provide material support for Taiwanese defense (which has been done since its passage). For this reason, it is also possible that the PRC could conclude that the US would not go to war to actually defend Taiwan.

The PRC would also likely employ escalatory responses to any US or coalition effort to defend Taiwan. For this reason, it is assumed that should PRC deterrence fail, then the PRC would follow with military action in a sequential fashion consisting of a series of precise, but limited offensive operations aimed at first neutralizing and then defeating ROC forces within a two-week window, followed by posturing their forces in anticipation of any potential relief force attempting to come to the aid of Taiwan. This operational approach is consistent with their conceptual “Active Defense” and would align with the “Near to Far” threat engagement concept. Addressing US and coalition forces first, without neutralizing ROC forces beforehand, endangers PRC forces and cedes the possibility of ROC counterstrikes on PRC CI and vital facilities needed for military operations.

Given that any US response to a PRC attack would be slower to materialize than ROC counter moves, there could be a limited timeframe in which the PRC could execute initial attacks to neutralize and then defeat the majority of the ROC military assets prior to potentially having to engage US and coalition forces. For this reason, the PRC will likely execute and action first against the “near” threat (ROC), ensuring PRC forces freedom of maneuver as well as ensuring overall conditions are set for the accomplishment of their strategic end state prior to engaging the “far” threat (US+) second, which could also be viewed as “defense of their end state”.

Another factor with this rationale is that for the US to generate enough combat force to contest the PRC over Taiwan, it will take considerable time for the entirety of forces to be postured for battle. This time also will include numerous shaping operations beforehand that aim to create favorable operating conditions for US and coalition forces, prior to directly engaging in direct operations against the PRC. The PRC may also estimate that this “window” is sufficient enough to address the “near” threat first and then utilize this “window” to attempt and resolve the dispute diplomatically prior to the US and coalition allies ensuring access, establishing required conditions, and generating sufficient combat power to contest PRC forces IVO and on Taiwan.

Operational Options for the US and Coalition Partners

For the US and potential coalition partners, there are multiple operational options available to contest and defend Taiwan from a PRC attack. The US could initiate a direct contest against the PRC as depicted in numerous civilian think tank models. The US could leverage its existing alliances and partnerships by conducting multiple, distributed, and dispersed area denial operations via ASuW and Anti-Air operations or the US could conduct stand-off blockades against PRC energy and commerce in addition to either of the two mentioned above. The methods for each option are also numerous as the US and coalition partners have numerous assets to conduct such operations with as well. Before any of these options occur, it is critical to first focus on several notable potential constraints that could influence US operations.

First, there have been numerous war games generated by academic think tanks, non-profit centers, and other civilian institutions and all place constraints on US forces and create scenarios in which US forces directly contest PRC forces within aerial range of the PRC mainland and limit US operations to PRC forces in the immediate vicinity, with restrictions on direct attacks against the PRC mainland. In these scenarios, political factors constrain US war plans and operations, limiting US military responses. The outcomes are therefore easy to predict.

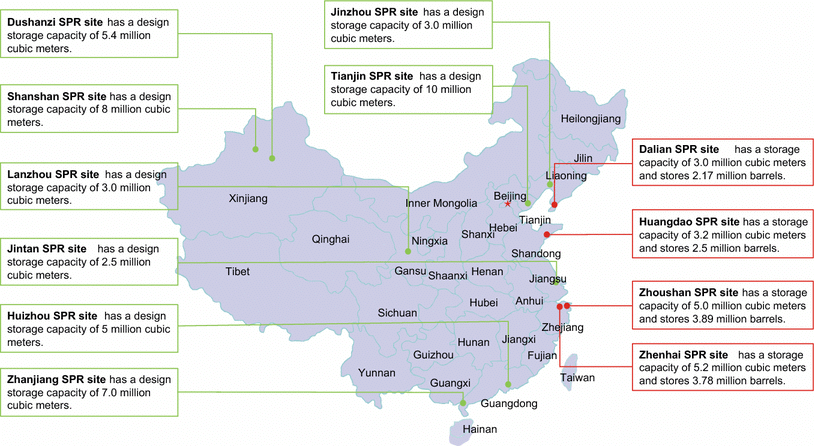

Another major constraint facing US forces (including coalition partners) will be political pressure or concerns that wish to limit the conflict to the immediate area and ensure it does not end up in a nuclear exchange between the PRC and US. While understandable, the PRC is at a significant disadvantage in the conflict were it to become nuclear. Further, the PRC would not likely initiate a nuclear attack against the US or its allies unless its survival was directly threatened. However, this concern has influenced multiple war games within US defense circles. As a result of this, it is possible that any US response would be constrained in nature and limited to avoid the potential of a nuclear exchange with the PRC. Such constraints could consist of the following: restrictions emplaced against US forces from targeting PRC forces outside of the immediate engagement area, restrictions against US forces from targeting the PRC mainland itself, including ports, airfields, bases, strategic assets, including POL storage sites, restrictions on US forces regarding weapon control statuses, restrictions on US forces requiring PID prior to any engagement, even in self-defense (given that OTH targeting in nature lacks PID) and restrictions on US forces achieving a decisive end state.

Potential Outcomes

These restrictions and constraints distinctively disadvantage US forces and in the event some or all are emplaced, jeopardize US forces and expose them to defeat. For these reasons, any constraints must be clearly defined and carefully mitigated prior to operations commencing. In the event any of the above examples were to be emplaced on US forces, the outcome would heavily favor the PRC, who will not likely emplace any such constraints on their own forces. Therefore, regardless of scenarios, if there are constraints on US forces, the likelihood of a significant US defeat would greatly increase.

Another constraint that warrants consideration is how the US operational strategy will unfold. As stated above, most (civilian) war games place constraints on US forces and also model US forces operating within 500nm of the PRC coast with surface and aerial forces exchanging salvos with PRC forces (in a linear fashion), while concurrently, multiple large-scale air battles over Taiwan and elsewhere occur. These scenarios, as well as the listed political constraints on US forces, are logically flawed and skew potential outcomes and decisively provide the PRC tactical advantages. An alternative consideration where US forces will not be constrained and will be allowed to employ both DMO and EABO operations against PRC forces in the event of war occurring must be considered equally to the scenarios where significant political constraints are emplaced on US forces.

With this, the US and its coalition partners are not constrained or limited. This entails that US forces will be authorized to engage and defeat all PRC forces, will be allowed to capitalize on superior weaponry, training, geographical positions, networked sensors, and robust battle management systems, networks, and leverage its superiority in the Informational Domain as well as engage PRC mainland targets, to include all relevant staging bases and CI and facilities such as C5ISR nodes and POL storage locations. In either case, prior to any conflict, US forces will be stationed in Japan, Australia, the ROK, Guam, and Hawaii, as well as various other locations across the globe. The forces forward deployed also work in tandem with military forces of their host nation partner.

For the purposes of this mini-series, it will be assumed US forces will be constrained with the following: the denial of initiating offensive operations against the PRC, targeting key PRC cultural and civilian government facilities, as well as critical infrastructure that could cause significant collateral damages to the PRC civilian populace. US forces will also be restricted from targeting energy pipelines outside of China as well as indiscriminate targeting of commercial shipping entering or exiting Chinese ports.

In Part IV, conceptual operational factors, methods, and a general overview of forces will be covered.

*Constraint is defined as self-imposed restrictions

**Limitations is defined as restrictions imposed by a 3rd party or international agreement

***Forward deployed forces will be assumed to have an OR rate of 90%

****PRC forces will be assumed to be at 90% OR rates

Kindly,

Mel Daniels

————————————-Nothing Follows—————————————