Debaltseve and Ilovaisk: Hybrid Warfare in Europe. Much has been said about the hybrid approach to warfare adopted by Russia in recent years. Words such as “Asymmetrical”, “Irregular” and “Unconventional” are usually used when describing Russia’s military operations in Ukraine. To the untrained eye, the Russian Art of War looks more than ever conventional. What is Hybrid Warfare? The war waged by Russia in Eastern Ukraine in the summer of 2014 and winter 2015 was in a scale not seen in Europe since the Yugoslav Civil War of the 1990’s. A type of warfare which, in scope and intensity, would shock a majority of Western soldiers and officers who have been trained instead in the art of counter-insurgency. The three most glaring demonstrations of this type of warfare are the Artillery Strike on Zelenopillya of July 2014, the Battle of Ilovaisk of August 2014 and the Battle of Debaltseve in February 2015. There, the Russian armed forces rolled out a blend of combined warfare, mixing aggressive armoured thrusts and encirclement manoeuvres with old school sieges, positional trench warfare, overwhelming use of artillery and high-end electronic warfare.

Background

Those battles find their origin in the Ukrainian civil-war, which itself finds its source in the pro-European Euromaidan revolution of 2014. Said revolution can trace its own roots all the way back to the days of the Russian Empire and the subsequent fragmentation of the Ukrainian population between Westward looking, Ukrainian speaking Western provinces and Russian speaking Eastward looking Eastern provinces.

We are not going to go too deep into the political background and precursors of those battles, this is for another upcoming article. Nevertheless, for clarity’s sake, we must summarily address the events that led to those battles. Here they are.

Anti-government protests erupted in Kiev on the 30th of November as President Yanukovych picked up a Russian bailout package instead of accepting a deal from the EU. As the police tried to crack down on the protests, protesters became more numerous and determined. Slowly but surely, violence on both sides increased and threatened to spiral out of control. With protests on the verge of turning into full scale riots. Protesters called for president Yanukovych to resign.

In December 2013, Republican Senator John McCain and Democratic senator Chris Murphy visited Kiev and addressed the crowds:

This visit and subsequent statement was seen by Russia as gross interference in its near-abroad/sphere of influence. The protesters, galvanised by the US support kept on occupying parts of Kiev while anti-government protests started being held everywhere in Western Ukraine (Pro-European). Meanwhile some pro-government protests started being held in Eastern Ukraine, where Yanukovych comes from and where people are rather more pro-Russian than pro-European. The situation went on to progressively degenerate throughout December and January, with both sides digging-in, politically and on the ground. By the 18th of February, the Lviv province (oblast) situated in the West of the country declared itself independent from the Ukrainian government (no longer recognising the Yanukovych administration) amid scenes of open warfare between armed Euromaidan protesters and riot police (Berkhut) using live ammunition.

Yanukovych left Kiev for Kharkov on the 21st of February while many ministers and deputies opted to stay at home or leave the capital, fearing for their safety. The following day (22nd of February), Ukrainian opposition deputies removed Yanukovych from power, breaching the Ukrainian constitution that required them to follow an impeachment process that would have involved the Constitutional Court of Ukraine. They elected Turchynov to be Chairman of Parliament, acting president and prime minister. This move angered the population of Eastern Ukraine (Yanukovych served as governor of Donetsk in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s). On the 23rd of February, members of theUkrainian parliament voted to abolish the Ukrainian Law on Language, meaning that the Russian, Romanian and Hungarian languages that were up until then protected were suddenly no longer recognised as official regional languages. This particular move sparked unrest in the Donbass region and in Crimea, where Russian is often people’s first language! Pro-Russian protests appeared in Crimea that day.

From the 24th of February onwards, on the orders of the Ukrainian parliament, many members of the Yanukovych administration and the party they belonged to (Party of Regions) started being dismissed, investigated or arrested. From the point of view of the population in the Donbass and Crimea ( as well as in Moscow), this looked like an anti-Russian witch-hunt. On the same day, under pressure from popular protests and some members of his own administration, Volodymyr Yatsuba, head of the Sevastopol city council, resigned. A Russian citizen was elected as Mayor of Sevastopol in his place. As the Ukrainian opposition strengthened its grip on Kiev, it lost control of Crimea. On the 25th of February, acting President Turchynov called for the formation of a government of national unity. The very same day, the Crimean police defected to the pro-Russian side.

On the 26th of February, Turchynov assumed the duties of supreme commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The very next day, on the 27th of February, as a government of national unity led by Arseniy Yatsenyuk started to preside over Kiev, “Little Green Men” appeared in Crimea. Throughout that period, daily anti-government protests were held in Donetsk. Events started to escalate on the 1st of March when protesters took over the Donetsk Regional State Administration. They remained in place for almost a week before being removed from the administrative building by the Ukrainian SBU. On the 6th of April, protesters in Donetsk asked for a status referendum on their region. Unrest spilled into Luhansk, where protesters seized the SBU headquarters.

On the 9th of April, Kiev launched its ATO (Anti-Terrorist Operation) aimed at quelling protests in the Donbass and the South of the country. On the 12th of April, armed protesters (including ex-Berkhut officers) seized the Ministry of Internal Affair building in Donetsk. This led the Chief of Office to resign. Subsequently, the Donetsk People’s Republic was proclaimed. Two days later, separatists and pro-Russia supporters (supported by Russian GRU elements) took over official buildings all over the Donbass as far as Mariupol (Cities impacted included Sloviansk, Mariupol, Horlivka, Kramatorsk, YenaKiieve, Makiivka, Druzhkivka and Zhdanivk).

The first armed clashes between Ukrainian security services and elements of the Dombass People’s Militia occured on the 15th of April near the Kramatorsk airfield. On the 16th of April, Donetsk TV station was seized by separatist protesters. The station promptly started broadcasting Russian Channels. On the 27th of April, separatists established the Luhansk People’s Republic. By the 4th of May, the DPR flag was hoisted over Donetsk Police Station.

On the 22nd of May, elements from the Ukrainian army were ambushed in the province (oblast) of Luhansk by between 300 and 500 armed militiamen. On the 26th of May, the pro-Russian Vostok Battalion seized Donetsk Airport. Anti-government protests in the East had turned into an armed rebellion. There was a civil war in Ukraine.

Ukrainian ATO and Russian counter-attacks.

While the Ukrainian ATO (Anti-Terrorist Operations) was officially launched on the 9th of April, it was slow to gain steam and was subsequently “relaunched” on the 22nd of April. When the Little Green Men appeared in Crimea, Ukraine had on paper 130,000 troops, including 16,000 on the peninsula. Of this theoretical figure of 130,000 soldiers, only 5,000 were combat capable. Beside the 25th Airborne Brigade, 30th Mechanized Brigade, 79th Airmobile Brigade, 80th Airmobile Brigade, the 85th Airmobile Brigade, and the 3rd and 4th Special Forces Regiments (which were all under-strength) the Ukrainian armed forces were just a motley crew of poorly trained and poorly equipped grunts. As such, to conduct its ATO, Ukraine created Company Tactical Groups, throwing together men and equipment from various units, hoping that a partial mobilisation of the Ukrainian Army would fill in the ranks. Two rounds of mobilisation were organised in June but fell far short of requirements. Ukraine’s ATO was therefore initially conducted by a handful of military units and various paramilitary groups, volunteers’ militias and oligarchs’ “private armies”.

Throughout May, June and July 2014, groups of Ukrainian volunteers (militias) equipped and advised by the Ukrainian army clashed with groups of Ukrainian volunteers equipped and advised by the Russian army. Despite the apparent shortcomings cited above, the Ukrainian army was successfully conducting its ATO and by July 2014, was near its goals of splitting the Donbass in two (roughly along the Luhansk and Donetsk demarcation line) and start securing the Russo-Ukrainian border. By early August, forces loyalist to Ukraine were controlling 60% of the Donbass.

July represented the high tide mark for the Ukrainian forces’ ATO in the Donbass: Russia was about to intervene directly into this conflict!

Artillery strike on Zelenopillya: Carnage on the Ukrainian plains

On the 11th of July 2014, the 24th, 72nd and 79th Mechanized Brigades of the Ukrainian army were situated outside of the town of Zelenopillya, 9 miles from the Russian border. The brigades had been spearheading an Ukrainian offensive and intended on pushing toward the Russian border with the goal of sealing the border and cutting off the separatists from direct Russian support.

They were spotted by a Russian UAV as they were assembling. Soon after the Russian UAV was sighted, Ukrainian C3 (command, control and communications systems) were jammed. Minutes after that, Ukrainian troops were engaged by a combination of BM-21 Grad Multiple Launch Rocket System and conventional artillery firing a mix of scatterable submunitions, thermobaric warheads and top-attack munitions. The Russian artillery units engaged the Ukrainians at a range of 15 km; from inside Russia proper.

The fire-strike lasted a mere three minutes, but in that span of time, it had put two out of three Ukrainian Brigades out of combat: At least 37 men were killed, the wounded were estimated to number between 90 and several hundred. Two brigades’ worth of vehicles were either damaged or destroyed. The 1st Battalion of the 79th Mykolaiv Airmobile Brigade was completely wiped out as its men were already inside their softtop vehicles when Russian rockets and shells landed.

Russia had just entered the Ukrainian Civil War… Russian mercenaries and GRU officers had been active in Ukraine since at least April, the artillery strike on Zelenopillya represents their first real conventional military steps into the Ukrainian civil war.

The Ilovaisk trap

After Zelenopillya, the Ukrainian leadership decided to focus on Ilovaisk: A town that controlled the supply route linking Donetsk to the Russian border. When Ukrainian army elements approached Ilovaisk on the 7th of August, it was believed the town was being held by only 80 rebels. Therefore, only 400 men were initially allocated to restore order in the city (while more units were being deployed to guard the Ukrainian flanks). Many of those men belonged to three volunteer battalions ( Azov, Donbas and Shakhtarsk). The initial Ukrainian assault was launched on the 10th of August with a couple of IFVs (BMP-1) and one MBT in support (T-64). Three tanks were initially earmarked for the operation but one broke down and one never received the order to depart.

Very quickly, the situation took a bad turn for the Ukrainian forces: Their sole tank was engaged and destroyed, one of the BMP-1 was lagging behind due to engine problems and they soon (unknowingly at the time) encountered Russian special forces: Russian GRU Spetnaz slipped in between the Azov and Donbas battalions and opened fire on elements of both batallions before withdrawing unseen (engaging and withdrawing), causing confusion and almost succeeding in convincing the Ukrainians that they were exchanging friendly fire. Ilovaisk was apparently a tougher nut to crack than at first anticipated and the Ukrainian troops withdrew.

On the 18th of August, the Ukrainian command resumed its offensive on the city, sending in almost 550 men belonging to 6 militias and 2 army units. Those men were supported by more armour and managed to reach the city centre by the next day. Operations inside the city went smoothly and the Ukrainian forces were in the process of mopping up what they thought were the remnants of the rebel held positions inside Ilovaisk when suddenly, on the 20th of August, rebel resistance inside the city seemed to harden and Ukrainian forces started to suffer casualties. They promptly called in for reinforcements and some reached them. It was a trap: On the 24th of August, conventional Russian army units crossed the border (estimated at 8 Battalion Tactical Groups / 6,500 men) and merged with local militias and DPR/LPR army units. Ukrainian commanders relayed this information to Kiev but the Ukrainian High Command seemed to be in complete denial. The following day (25th of August) Ilovaisk was cut off from the South as Russian forces clashed with Ukrainian elements around the city. Several militias loyal to Kiev hastily withdrew when they realised they were fighting elements of the Russian army. Ukrainian army checkpoints and strongholds were denied permission (from Kiev) to open fire on Russian columns as those were moving around without visible flags or markings. Ukrainian troops were therefore initially on the back foot, only opening fire when engaged first (return fire), basically handing over the initiative to their attackers.

By the 27th, the city was completely surrounded. The Ukrainian forces that had surrounded Ilovaisk were themselves surrounded. The Russian army had advanced so quickly and the Ukrainian army communications were so bad that many Ukrainian militiamen and servicemen inside the city learned that they were surrounded not from their own hierarchy but from family members calling them and informing them of what they had seen or heard on the news, back home! A relief column sent to break the encirclement was stopped in its tracks by a Russian artillery barrage and subsequently defeated the next day (28th of August) by Russian paratroopers.

Ukrainian forces inside Ilovaisk tried to dig in, but it soon became clear that no reinforcements or supplies would reach them. They were shelled relentlessly and running short of food and ammunition. On the 29th of August, the local Ukrainian commander negotiated a retreat with his rebel/Russian counterpart. The Ukrainian army started to withdraw on the 30th of August, leaving the town in two columns (North and South).

During their retreat, the Northern column drove straight into a Russian ambush roughly 10 kilometres from Ilovaisk. The Ukrainian column was first attacked by a Russian armoured thrust, before being engaged by Russian artillery which drove the remnants of the column straight into a second armoured ambush. The Southern column was also attacked but stood its ground, inflicting casualties on the Russian forces (two Russian army T-72B3 (6th Tank Brigade/20th Guards army) were destroyed). The Ukrainian units were however soon encircled and around 50% of their manpower were reported wounded by the end of the day. They agreed to surrender their weapons to the Russians the next day. In exchange, they were allowed to be evacuated back to their own lines under Red Cross supervision

The Russian intervention and the subsequent two ambushes on withdrawing Ukrainians were responsible for the loss of dozens of vehicles, 500 men taken prisoners, 500 wounded and over 1,000 men killed. This represented the bloodiest battle (day) of the war for the Ukrainians, so far.

After the battle of Ilovaisk , both sides dug-in and consolidated their positions.

The Debaltseve Cauldron

Debaltseve came under separatist/pro-Russian control in the opening weeks of the Ukrainian civil war, as early as April 2014. The Ukrainian army was successful in counter-attacking and recapturing the city in July of the same year and reinforced its positions there. Debaltseve occupies a strategic junction between the Donetsk People’s Republic and the Luhansk People’s Republic, controlling the main roads and railway links between the two entities. The Ukrainian position there represented not only a wedge or bulge in the middle of the Donbass Republics frontline, but also a logistical and economic/financial drain on them. There was also the risk of another Ukrainian push along that axis, which could have the potential to split the separatist territory in half. From a separatist (or Russian) point of view, there is no doubt that Debaltseve had to be (re)conquered.

After Ilovaisk, (Russia’s) Southern Military District increased the number of Russian troops in Ukraine from around 6,500 men to between 9,000 and 10,000 men according to various estimates. The Russian Battalion Tactical Groups in Ukraine (BTCs) were battlegroups created with units taken from various Russian Field Armies with men originating from every single Russian Military District. Those BTCs became the nucleus of separatists formations, reinforcing them and providing them with a core of “shock troops”, experience and know-how. Smaller separatist formations that did not receive an injection of Russian soldiers were given military advisors in the form of a squad of Spetnatz, GRU operatives or Russian officers. Separatist outfits from the DPR and LPR were then absorbed into a coherent structure with an integrated command supported by Russian staff officers placed under the authority of Russia’s Southern Military District headquartered at Rostov-on-Don.

Ahead of the battle of Debatlseve, the Ukrainian army had positioned an estimated 8,000 troops in and around Debaltseve as well as an estimated 5,000 men elsewhere along the line of contact between loyalist Ukraine and separatist Donbass. Ukrainian troops in Debaltseve were mostly volunteers (irregular militiamen) belonging to the army’s 40th Motorised Infantry Batallion as well as National Guard militiamen and volunteer outfits such as the Donbass Batallion and the Dzhokhar Dudayev Batallion (pro-Ukrainian Chechens). They were supported by elements belonging to several regular army units such as the Ukrainian 30th Mechanised Brigade, 24th Mechanised Brigade, 92nd Separate Mechanised Brigade, 79th Air Assault Brigade, 1st Tank Brigade and the 128th Mountain Assault Brigade. The Ukrainian defence of Debaltseve rested on a blend of fortified strongpoints (strategic heights, villages and checkpoints) and trenches. Their main supply line into Debaltseve being the M3 road linking this town to Artemivsk in the North.

In the opposite corner, the breakaway republics of Donetsk and Luhansk had mustered around 10,000 to 15,000 troops. Many of them were issued from their respective volunteer battalions and amalgamated into a new cohesive outfit called “United Armed Forces of Novorossiya”. Were also involved the Prizrak (Ghost) Mechanised Brigade (operating in LPR but with autonomous command) and the Cossack National Guards (regiment sized, autonomous, answers to Don Cossack Host leadership which is traditionally a Russian ally. Russia’s conventional troop contributions included one Tank Brigade (5th Guards), two Motor Rifle Brigades (8th Guards and 18th Guards), one Spetnaz Regiment (25th) and one Artillery Brigade (232nd Rocket Artillery Brigade).

It is difficult to estimate how many Russian servicemen were really involved in the Battle of Debaltseve itself for several reasons:

– Russian regulars and Donbass irregulars merged seamlessly into cohesive units.

– The frontline was not restricted to the Debaltseve pocket as actions took place along a front which was over 200km in length (more on this later on).

As the Ukrainian high command estimated at the time that it was faced by roughly 19,000 men in and around Debaltseve, one can estimate the composition of the opposing forces around the Debaltseve pocket to have been composed of 50% irregular militiamen (volunteers, local or not) and 50% Russian army troops, achieving parity.

On the 17th of January, Russian and rebel artillery started softening the Ukrainian held towns of Vuhlehirsk, Nikishyne, Ridkodub, Chornukhyne, Sanzharivka, Triotske and Popasna. This represents an initial theatre of operations 44km long and 22km wide. From the 22nd of january onward, Ukrainian units witnessed their communications being severely degraded (Russian EW jamming) while artillery started to engage Debaltseve directly… The rebels (and the Russians) were coming!

Svetlodarsk was repeatedly attacked by the separatists from the 22nd/23rd of January onwards, threatening to cut the M3 linking Artemivsk to Debaltseve. When their offensive was repulsed, the rebel forces switched to attack Height 307.5 (near the village of Sanzharivka). This particular point overlooks the M3. Between the 27th and the 29th of January, the villages of Vuhlehirsk, Sanzharivka, Chornukhyne, Ridkodub and Nikishyne as well as Height 307.5 were alternatively shelled and assaulted. On the 29th of January, Vuhlehirsk fell and separatists managed to remain in control of the town despite ferocious Ukrainian counterattacks.

On the 3rd of February, a 24 hour truce was agreed by both sides.

In the early morning of the 9th of February, while Ukrainian forces were distracted by what looked like an all-out armoured assault coming from the north, Russian Spetnaz units infiltrated their lines and mined the M3, capturing the town of Lohvynovo in the process. This move effectively severed the Ukrainian main supply line. In the fog of war, Ukrainian communications completely failed and for the remainder of the day, Ukrainian units on both sides of the Lohvynovo chokepoint were not informed that the M3 was cut off. As a result, supply convoys attempting to reach Debaltseve and convoys trying to evacuate casualties out of the city repeatedly fell victim to Russian ambush and artillery strikes along that axis. By the 10th of February, the Debaltseve pocket was as good as closed by the separatists: They controlled the M3 and the smaller roads they did not yet physically control were effectively kept shut by Russian artillery. A hastily organised Ukrainian counterattack on Lohvynovo failed on the same day. For the next 5 days, the Ukrainian army threw everything it had in the Debaltseve pocket at Lohvynovo in an attempt to reopen the M3. Most regular Ukrainian army units were involved (24th, 30th and 92th brigades, 1st tank brigade, 79th airborne brigade) as well as the Donbass Battalion. They failed to reopen the road.

On the 15th of February, Ukrainian servicemen received text messages on their personal mobile phones. The messages promised them safety should they choose to surrender: Some Ukrainian officers inside the pocket received more personalised texts, including messages containing private information such as addresses of relatives, where their children were schooled and so on… The messages were sent by Russian EW units in order to disrupt the defenders’ morale. On the 16th of February alone, Russian and separatist artillery units conducted over 100 strikes on Ukrainian positions. By then, Russian sensors were well in place (drones, radars and EW units) meaning that the strikes were increasingly accurate, targeting any visible concentration of soldiers and any vehicle on the move. Ukrainian artillery units were engaged by counterbattery almost immediately as soon as they let off a shot and any vehicle, position or individual using any means of communication (radio, mobile phone and satellite links) were also almost immediately targeted. On the same day, a separatist offensive managed to finally close the Debaltseve pocket and the Ukrainian eastern flank started to collapse.

The following day (17th of February), the pro-Russian troops took control of Debaltseve’s railway junction.Unable to be resupplied, low on ammunition, unable to evacuate their wounded and in the face of a leadership that was completely disconnected from reality and was lacking control and situational awareness, some Ukrainian units attempted to break through to safety on their own accord.

Finally, on the evening of the 17th of February, the Ukrainian High Command gave its units on the ground the order to evacuate. They communicated to them an overly complex evacuation plan (5 columns that had to depart following two different roads according to a strict time table!) while giving them too little notice to organise themselves. Several Ukrainian units never received the order to evacuate while others were in no position to follow such a strict plan or timetable: Any concentration of vehicles or troops was being targeted by the separatists and the pro-Russian faction controlled every road leading in and out of the Debaltseve pocket. Throughout the night, Ukrainian commanders attempted to lead their individual units to safety in total darkness and radio silence. Progress was slow. Too slow… As daylight rose, the retreating Ukrainian convoys became sitting ducks: Armoured thrusts, artillery and ambushes cut their columns to shreads, prompting individual soldiers to abandon their vehicles, drop their kit and run to safety. The retreat turned into a rout and Ukrainian units suffered more casualties on the morning of the 18th of February while trying to reach safety than during the heavy fighting that took place in the weeks preceding this event. Losses incurred during the retreat from Debaltseve amounting to between 50 and 75% of their remaining manpower.

Debaltseve was firmly in the hands of the serapratist forces as of the 19th of February. Officially, Ukraine admitted to 269 deaths in its ranks for the Debaltseve Battle. The true cost, according to unofficial Ukrainian sources, is closer to 3,000 deaths. The separatists admitted to 58 KIA, but the real figure is estimated at 2,900. A US Army report stated soon afterwards that “The battle for control of Debaltseve destroyed the 128th Mechanized Brigade and the Donbas Battalion as fighting formations.” As far as Ukrainian estimates can be assessed, only 150 men out of a total of 2,000 men belonging to the 128th Mechanised Bridade made it out alive.

Battle Analysis: The “New” Russian Art of War

On the ground in Ilovaisk and Debaltseve, the Russian intervention was centered around its BTGs (Battalion Tactical Groups). The Russian BTG, while a tactical formation, has access to operational capabilities normally found at echelons far above a tactical battalion, greatly increasing its impact on the battlefield. It is created and equipped ad-hoc for a particular mission. In this, it is somehow reminiscent of the WWII era German Kampfgruppen. In Ukraine, Russian expeditionary capabilities were downsized from the Divisional level/size to the Batalion level/sized. Those BTGs used horizontal command mechanisms; eliminating the middle men; shortening communication and command channels in the process. There were no “joint operations” in the Russian intervention in Ukraine. The BGTs were coherent units with their own Special Forces (Spetnaz), infantry and armour; bringing in their own artillery, reconnaissance, and logistic assets; all under one unified command. Russian BGTs in the Donbass seamlessly amalgamated with irregular forces, private security contractors and Cossacks. Those BGTs conducted their own reconnaissance, using organic assets as varied as Spetnaz, militiamen, local partisan forces in plain clothes with good knowledge of the surroundings, drones, Electronic Warfare units, Battlefield Radars and Counter-battery Radars. The information collected by those assets travelled almost instantaneously from recon assets to artillery batteries, without having to climb through the complex chain of command and the multiple layers of clearance and approval usually found in Western style Joint Operations. In short, in the words of military analyst Phillip Karber: “The Russians have broken the code on reconnaissance-strike complex, at least at the tactical and operational level.” In Ukraine, those BTGs achieved what has been called near-instantaneous sensor-to-shooter capabilities.

Moscow-led forces achieved “a high level of synergy” during the fighting, an American military report stated: Synergy between reconnaissance and artillery, between infantry and armour, between regular and irregular forces within each BTGs and between the various BTGs and other units simultaneously operating across the theatre of operations. Indeed, it is first and foremost the coordinated employment of tanks, infantry, artillery, and other battlefield assets in a timely fashion that enabled the separatist forces (supported by Russian assets) to rout the Ukrainian units evacuating from both Ilovaisk and Debaltseve. While the “Novorossiya armed forces” were indeed a hybrid army, one where militant groups and professional servicemen were seamlessly integrated into ad-hoc battlegroups, the way those units operated and the assets they employed during those battles were textbook conventional.

Additional Russian support materialised in the form of cross-border artillery and C4ISR (Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance and Reconnaissance). Moscow also used paramilitary organisations / security contractors to supply manpower as well as Soviet era heavy weapons to separatist forces in Eastern Ukraine. Those Russian contractors also acted as instructors, providing separatists with training in artillery, engineering and military planning. An estimated 200-400 Wagner contractors participated in the offensive on Debaltseve.

While we like to talk about the involvement of regular Russian army units in Ukraine, one must not forget that volunteers and local militias were the ones that bore the brunt of the fighting in both Ilovaisk and Debaltseve. Indeed, talking about Debaltseve, Cossacks were the ones leading the fight up until the 24 hour truce agreed by both sides on the 3rd of February 2015. There is no doubt that Russian servicemen were there, advising them, reinforcing them and supporting them with the type of hardware and resources irregular militias cannot usually acquire or operate. There is also no doubt about the fact that at the peak of the Russian intervention in the Donbass (in Winter and Summer 2015), Russian servicemen never represented more than 50% of the separatist forces fielded in Eastern Ukraine. As separatist forces grew (trained, financed and equipped by Russia but manned by locals), the proportion of Russian servicemen diminished overall. Russian forces in Ukraine peaked at between 7,000 (UK estimates) and 12,000 (US estimates). Ukraine estimated them at 9,000. At the same time, separatist armed forces in the Donbass peaked at over 42,000 men by summer of 2015! Just as we explained in our article on the events in Crimea, the Russo-Ukrainian war is effectively first and foremost an Ukrainian civil war, pitting Ukrainians against one another. (Article on the Crimean crisis here: https://defensionem.com/why-the-ukrainian-conflict-is-first-and-foremost-a-civil-war/)

On the offensive, in typical Soviet/Russian fashion, separatist troops constantly varied the direction of each assault/thrust so as to retain momentum and initiative and keep the defenders unbalanced. This fact was obvious at both Ilovaisk and Debaltseve. This wasn’t just done at the tactical level, around Debaltseve, but actually replicated over the whole theatre of operations so as to pin Ukrainian troops away from Debaltseve proper: The town of Shyrokyne, situated 140km South of Debaltseve was shelled and assaulted on the 15th of February, just as the Ukrainian army was trying to reopen the M3 road leading to Debaltseve to relieve its troops besieged there. In fact, separatists threw a large scale assault toward Shyrokyne on that date, stating that the strategic Ukrainian city of Mariupol (20km West of Shyrokyne) to be the main objective of their offensive. The separatist offensive in that area was sustained for several days, pinning Ukrainian resources away from Debaltseve. The following day (16th of February), the town of Shchastia situated 75km North of Debaltseve was also shelled. This was followed by separatist troop movements in the area and statements indicating that the strategic city of Karkhov/Karkhiv was also one of the objectives of the separatist offensive! The distance between Shyrokyne and Shchastia represents a front just over 200km wide. One that the underresourced and overstretched Ukrainian forces had no chance of adequately covering. On February the 18th, fighting broke out around the ruins of the Donetsk Airport, 57km South of Debaltseve, again, pinning Ukrainian troops away from the centre of gravity of the separatist offensive. It is obvious, then, that the operations around Debaltseve represented a demonstration of conventional warfare on a large scale, the likes Europe had not witnessed since the civil war in Yugoslavia in the 1990’s. So then why is this war called “hybrid”?

According to Robert R. Leonhard, Hybrid Operations “…are characterized by undeclared actions, that combine conventional and unconventional military operations, while coupling military and non-military actions in an environment in which the distance between strategy and tactics has been significantly reduced, and where information is critically important. The form of warfare, called a variety of things to include, hybrid warfare or new generation warfare, is a whole-of-government approach to war that links the elements of national power and small-scale tactical action”.

The new Russian Art of War (hybrid warfare) creates synergies between conventional, unconventional, information, and cyber operations. The end-game is to make the job of tactical formations on the battlefield easier and increase their impact way beyond what such a formation could achieve otherwise. See it as a force multiplier applied to an already softened battlefield. This doctrine rests on the ability to seize the initiative, coordinate political and military action and use “maskirovka” (ruse/deception) on the battlefield. Some experts note that there is little distinction in this doctrine between peace and war: The activities are going on, constantly, in the shadows. Disinformation campaigns, cyberattacks, propaganda at international, national and local level, local alliances or pacts, local investments/corruption… The cogs of this machine are always running. And if and when needed, the transition from shadow operations to large-scale conventional warfare can be immediate and seamless. The use of covert operations and local/partisan forces is preferred, but Moscow is more than capable and willing to operate overtly with conventional combat power should it be needed to achieve its end. Carl von Clausewitz said: “War is simply the continuation of political intercourse with the addition of other means.” Likewise, in Russian Hybrid Warfare, tactical action is either the natural follow-up of a campaign in the event that the covert / unconventional actions that were taking place were unsuccessful in achieving the initial operational and strategic objectives; or the natural follow-up on a battlefield already softened up by said successful covert / unconventional actions. Russian hybrid Warfare seeks to blur the lines and evade detection and capabilities. It disrupts advantages through unconventional and asymmetrical means. It delays an opponent’s reaction through deniability. In the Gerasimov Doctrine, the physical and temporal distance between strategic, operational and tactical levels have been drastically shortened and they all share overlaps.

Psychological Warfare is at the centre of Russian Hybrid Warfare: The control and dissemination of information is paramount because at the heart of it reside the hearts and minds of the population. This weapon can be wielded in various ways:

- When Russia hacked into US political parties during the 2016 presidential campaign, Russian hackers forced their way onto American servers, seized information that could be “weaponised” and then released it through a variety of media and channels in order to discredit American politicians in the eyes of both the American public and the international community. The end-game here was for American citizens to lose confidence in their own institutions and leaders.

- In Eastern Ukraine and Crimea, many facets of this information warfare could be seen simultaneously. Russia has long cultivated its ties with the Russophone communities in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine, emphasising on shared religion, common history and heritage, common traditions and common language. Russian authorities have always been active in Sevastopol (Crimea) and in Eastern Ukraine, giving passports to people with Russian roots who made the demand (65% of Crimeans were Ethnic Russians before the war) and allowing Ukrainians to travel to Russia visa free and making work permit available to them easily. Before the war, Russian companies represented the largest foreign investor in Ukraine (7% of the total). Millions of Ukrainians travelled daily to Russia to work or do their shopping. The Russian-Ukrainian border was the second largest migration corridor in the world behind the USA-Mexico border. A third of Ukrainians leaving their country established themselves in Russia. Many people in Crimea and in the Donbass spoke Russian and therefore followed Russian media and Russian news. When Euromaidan came to the fore in Kiev and when the lawfully elected president of Ukraine was deposed in a pro-European coup, people in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine tuned in to Russian news to see what was going on. When members of the Ukrainian parliament tried to downgrade the status of the Russian language within Ukraine, this information was relayed by Russian media instantly. People in Crimea and in the East felt allienated, attacked, rejected: Almost one quarter of the population in Ukraine listed Russian as their first language before the war, meaning that Russian was also the first language of many ethnic Ukrainians living in the East). By the time Russia intervened militarily in Ukraine, a majority of the local populace actually supported the Russian intervention (43% of Ethnic Russians in the Donbass and Crimea supported the Russian military intervention). This is how both DPR and LPR managed to raise so many militias so quickly. The support was there . And said support had been nurtured and cultivated (by Moscow) long before the actual war in Ukraine… Thanks to those links and thanks to Russia’s clever use of communication (media and others) before and during the events, the legitimacy of this (Russian) intervention was never questioned by the majority of the local inhabitants in Donbass and in Crimea. There was a local consensus that Russia was a protector and a force for good well before the events of 2014. We see Russia as this rogue country using brute force to dominate its neighbours when in fact, Moscow has given us several lessons in how to wield soft power to achieve strategic/geopolitical goals.

- It is during the Crimean campaign that the Russian Hybrid War was employed the most effectively. As discussed above, Russian influence, which was viewed as beneficial by a majority of citizens on the peninsula, made Crimea ripe for action very early on (Operations started on the 22th of February). Inside their bases on the peninsula, Ukrainian armed forces soldiers and officers were torn between oath and duty to Kiev on one hand and loyalty to their roots on the other. Torn between what they could see and hear on Ukrainian and Russian news channels. They were defeated before the Russian “Little Green Men” even arrived in Crimea. The morale of the Ukrainian military was broken. There was no fighting. No battle. 10,000 Russian men using nothing heavier than APCs (BTR-82A) took control of 190 Ukrainian bases and 16,000 Ukrainian servicemen in a matter of weeks. The last ones surrendering or being taken over around the 22nd of March. Nothing more than smoke bombs, intimidations, negotiations and stun grenades were used. 50% of the Ukrainian troops defected to the Russian side and so did the First Deputy Commander of the Ukrainian Fleet. The Little Green Men were a maskirovka to delay the reaction of the Ukrainian leadership (and the international community) by creating a fog of war centered on the denial that any russian troops had been deployed at all. While security experts were trying to determine where those unmarked soldiers and self-defence units were coming from, the peninsula was sealed from the rest of Ukraine inside of 24 hours. 5 days after the apparition of the Little Green Men, the Crimean authorities officially requested Russian military assistance and Russian troops burst out of their bases. On the 16th of March (22 days since “D-Day”), a referendum was held across Crimea giving the local population a choice between Russia and Ukraine. Two days after that, on March the 18th, the Crimean and Russian authorities signed a treaty making the Ukrainian Black Sea Peninsula a part of Russia once more. The whole operation lasted 24 days. In 24 days, Russian GRU officers led a local rebellion (which was supported by the local population), unmarked soldiers appeared, seized government buildings and sealed the roads between Crimea and Ukraine. Then a “legal” political process appeared in parallel to the Russian underground operations (Crimea’s official request for military assistance). This official procedure was followed by two more political processes (referendum and reunification treaty) while unmarked soldiers were still in the process of seizing Ukrainian military assets and sending Ukrainian servicemen home. Russian president Vladimir Putin admitted to the involvement of “some” Russian servicemen in the events in Crimea after the referendum results of March the 16th were published. “Russian Soldiers are securing the Russian Naval base and have fanned out of their base to ensure the safety of the population,” he said. “But the situation is different, now, Crimea has joined the Russian Federation”. A full year later, in March 2015, Putin stated “Russian troops were deployed in Crimea. It was necessary to protect locals in predominantly Russian-speaking Crimea from violence and repression by Ukrainian nationalists”. Christian Marxsen highlights that those statements deliberately blur the line between military and nonmilitary action, making it more difficult to determine or agree whether an armed attack has actually occurred or not, especially when the aggressor claims to act in defense of one of the main principles of the UN Charter (Right to Self-Defence). Since 2014, Russia has made use of several legal principles to justify its use of force in Ukraine and Crimea: The protection and self-defense of Russian nationals living in the Donbass and Crimea and the direct invitation for intervention by Donbass and Crimean leadership (as well as that of ousted president Viktor Yanukovych). In studying the Crimean campaign of 2014, Janis Berzins (from the National Defense Academy of Latvia) identified tennets of Russian “New Generation Warfare”: Influence is prioritized over destruction; inner decay over annihilation; and culture over weapons or technology.

- There is a darker, more violent side to Russia’s Hybrid Warfare as seen in the Donbass, and battles such as Debaltseve, Ilovaisk and the fighting for Donetsk Airport. Russia again blended conventional and unconventional warfare. In March 2014, Russia had massed 40,000 troops along the Ukrainian border. Moscow also had 25,000 troops already present in Crimea and sent in another 10,000 “Shock Troops” to the peninsula to seize control of vital infrastructure, administrative nodes and neutralise Ukrainian armed forces units based there. That’s roughly 75,000 troops ready for action, already in-situ or on jump-off positions ready to deploy. Those were faced by 5,000 combat capable Ukrainian regular troops. To this, one could add the capabilities of the Russian Black Sea Fleet, which was more than capable of blockading Ukraine or conducting landing operations (Ukraine lost 51 ships captured by the Russians during the Crimean campaign, leaving its navy with just 10 vessels). The Russian Air Force was also in a much better position to conduct operations than its Ukrainian counterpart: Ukraine had about 220 serviceable planes of all types at the time. Russia was therefore in a position to roll into Ukraine and bulldoze its way through most of the country in a matter of weeks. Yet, Moscow followed another route, preferring instead to send fewer, unmarked troops on the ground and refraining from engaging its air forces and Navy in the process. Looking at the fighting in the Donbass and knowing the capabilities the Russians had just on the other side of the border, sitting unused, one could not help but think the battle for Debaltseve, Ilovaisk or Donetsk Airport could have ended much faster. This is another psychological facet of Russian Hybrid Warfare: Drag the conflict over time, making each battle a slow, costly grind for the leadership in Kiev and its armed forces. Modern Siege Warfare is grim for the defenders, having nowhere to hide and enduring massive artillery strikes. The purpose of this particular type of Siege Warfare was to slowly and deliberately destroy Ukrainian equipment and personnel. Russian artillery alternated between massive barrages and pinpoint accuracy strikes. Artillery fire missions were punctuated by separatist armour and infantry assaults on Ukrainian positions. For the defenders, it must have felt like a never ending vicious circle. The slow attrition of soldiers into the meat grinders that were those battles likely had a psychological impact on the Ukrainian people. Making Ukrainian civilians less likely to willingly participate or support the government’s actions or the Ukrainian armed forces or the volunteer battalions was part of the Russian strategy in the Donbass. Eroding the Ukrainian public’s faith in their own leadership and army, sowing doubt as to whether they were capable of successfully prosecuting a military campaign in the East. In Debaltseve, Ilovaisk and at Donetsk Airport, the Russian strategy was pretty simple: Bait the Ukrainian forces into a situation by threatening a strategic area. Once the Ukrainian forces are fully committed, swiftly surround their position and make them endure a bloody siege. Alternate artillery strikes and armoured thrusts to exhaust them through attrition and exhaustion. The Ukrainian troops allowed to evacuate from Ilovaisk and Debaltseve were suddenly faced with mobile (armoured) warfare and yet more artillery strikes, engaging them in the open, turning orderly retreats into routs, defeating a little more the spirits of the brave Ukrainian defenders. At Donetsk Airport, the Ukrainian troops withdrew when in their own words “There was nothing to hold onto anymore”: The airport was a field of ruins, a lunar landscape. It was completely devastated and there was nothing of value left to defend. As one expert noted: “A campaign’s morality or legitimacy is determined by the interests and will of the people supplying it, fighting in it, voting on it, and suffering from it. Exhausting popular will can damage an enemy more than seizing territory or inflicting physical damage”. Analysing the situation, Janis Berzins commented: “…The Russian view of modern warfare is based on the idea that the main battlespace is the mind and, as a result, New Generation Wars are to be dominated by information and psychological warfare, in order to achieve superiority in troops and weapons control, morally and psychologically depressing the enemy’s armed forces personnel and civil population. It is a true total war battlespace that encompasses political, economic, informational, technological, and ecological instruments…”

Parallels and comparisons with the Russo-Georgian War of 2008 and other conflicts

- When the Russian troops belonging to the 58th Army entered Georgia, they were wholly unprepared for the fight. Russian deficiencies in C4ISR were glaring: Russian troops relied on brute force and local numerical superiority to advance, completely lacking situational awareness, unable to prosecute simple reconnaissance missions ahead of the main thrusts and lacking intel on the exact whereabouts of Georgian troops. Poor communication at every level was another Russian hallmark during that campaign, with soldiers lacking individual radios and suffering from a lack of compatibility between radio sets used by the various services deployed in the theatre of operations. Another problem was low readiness levels and badly trained troops, forcing Russian military planners to rely on rigid deployment techniques ( They were not proficient in manoeuvre warfare). Bad leadership was pervasive. And finally, obsolete hardware (80% of vehicles and hardware had not been replaced or modernised since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991).

If Russian operations in Crimea and the Donbass proved something, it is that the reforms launched almost straight after the conclusion of the 5 days war in Georgia bore fruit and were implemented rather quickly indeed.

- Cossacks! Those paramilitary organisations/communities were the traditional guardians of Imperial Russia’s borders. They were shunned within the Soviet Union but have experienced something akin to a renaissance under the presidency of Vladimir Putin. In Georgia, Cossack militias deployed alongside regular Russian army units for the first time since WWI. They were amongst the first troops loyal to Moscow deployed in the Donbass, bearing the brunt of some of the most intense battles in the breakaway provinces.

- 2008 (during the Georgian campaign) was the first time the Russian leadership made use of media of all types to launch an information offensive on the global stage, win hearts and minds and control the narrative.The offensive ended up going all the way to the UN stage where Moscow spoke about the defence of oppressed Russian minorities wherever they are. This was most certainly a taste of things to come. Since then, Russia has been tech and information savvy and has been extremely active and proactive in trying to impose its narrative and point of view on many topics and events in general and on the situation and operations in both Ukraine and Syria in particular

- Moscow integrated cyber-attacks as part of its main battleplan in Georgia. The Russo-Georgian conflict was the first time Russia launched cyber-attacks and conventional forces at an enemy simultaneously. The results at the time were no more than a nuisance for Tbilisi, rather than a real threat. Today, cyberattacks are fully integrated into Russian military thinking and operations.

- Russian Army efforts to seize and retain the initiative and keep the enemy on the back foot were seen at the strategic level in Georgia with the opening of a second front. Units switching or alternating the direction of thrusts and offensives to accomplish a similar effect at the tactical level were witnessed not only in the Donbass (executed by separatist forces and Russian units) but also during the battle of Aleppo in 2016 and in subsequent Syrian battles, executed by Russian advised Syrian army units.

- Finally, the seamless blending of regular (Russian) and irregular troops and the propensity of Russian units to operate with no distinctive signs or with local militia patches was not only seen in the Donbass but also in Syria: Russian SF were identified wearing Hezbollah shoulder patches while patrolling with elements belonging to the Shia militia on several occasions. Meanwhile, in September 2017, when 29 Russian Military Police officers were surrounded by Al-Quaeda elements near Hama, the Russian commander of Hmeimim sent in a relief force composed of Russian regulars, NDF militiamen and SAA soldiers. The operation was successful.

(More on the Russo-Georgian war of 2008 here: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Analysis-Russo-Georgian-war-2008-Defensionem/dp/1791677126)

Long-Term Russian Strategy in Ukraine: Political and Military goals

Russian security thinking assumes that the nation is surrounded by enemies and therefore must maintain a territorial buffer to protect Russian sovereignty. Since the times of Imperial Russia, Moscow has tried to ensure the realm is surrounded by weak, neutral or cooperative neighbours. Historian Sarah Paine, writing about Russian policy, states: “Russian strategy had long been to surround itself with weak neighbors and to destabilize those who threatened to become strong. This was a logical strategy for a large continental empire.” Those neighbours represent Moscow’s buffer zone and sphere of influence. It is their very version of the Monroe Doctrine: Foreign influence is not welcome and must be countered within this area which they call their near-abroad. With regards to Ukraine, the Russian intervention in the Donbass and in Crimea fits well with this doctrine: With Kiev about to take a 180 degree turn toward NATO and the EU and away from Moscow, and with all the implications attached (NATO troops in Ukraine?) Russia had to intervene. Strategically speaking, the loss of their base in Sevastopol would have meant a weakened Black Sea Fleet bottled up in Novorossiysk and the Black Sea suddenly becoming a NATO owned and operated lake… By occupying Crimea (officially) and the Donbass (Moscow doesn’t recognise or admit its military presence in the region), Russia has crerated a territorial dispute with Ukraine, impeding Kiev’s wishes to rapidly join NATO and the EU. Said occupation also weakens the Ukrainian economy. The war has cost Ukraine roughly 15% of GDP per capita per annum since 2014! Ukrainian exports to Russia have dropped by 80%. Russia was (before 2014) Ukraine’s first customer. The situation would not get any better should Kiev manage to reconquer the lost territories: It is estimated that the damage in Luhansk and Donetsk Oblasts are so bad that it would cost roughly $21 billion to restore both infrastructure and economy in the region. Too much for Ukraine to shoulder alone. Especially as Kiev would have to do so in what are now two overtly separatist and hostile provinces. Kiev has lost the battle for the heart and mind of its own population in the Donbass, first with Euromaidan, then with the blockade put into place against the breakaway regions. Both LPR and DPR are now conected to the Russian electrical and gas grids. The Ruble is used for all transactions in the Donbass. Moscow pays the pensions of the citizens living in the area as well as the salaries of civil servants operating in the Donbass. Russian goods are found in shops. Moscow spends an estimated $6 billion annually to prop up the Donbass’ economy and take charge of its administration.

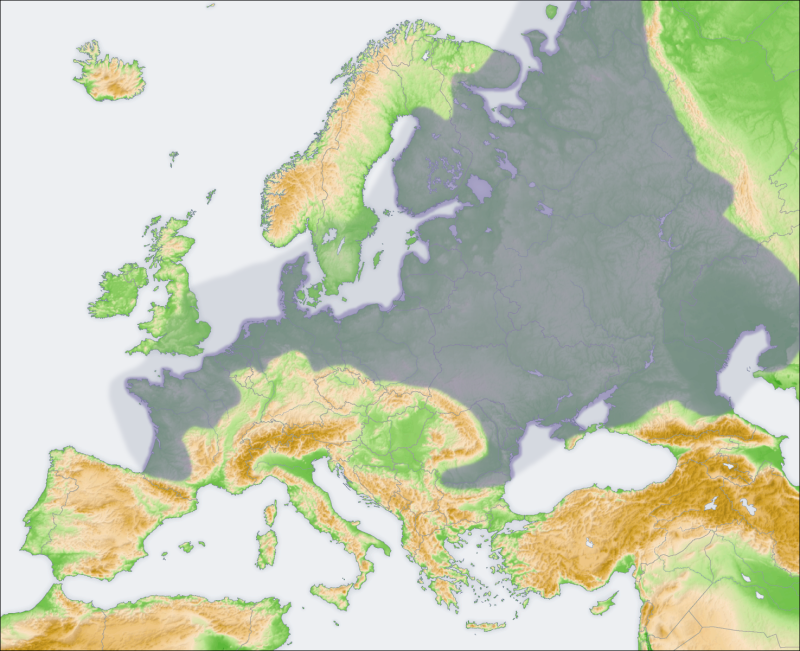

Russia lashing out at Ukraine doesn’t just find its roots in politics and in what Moscow sees as a Western-supported coup or at the very least, serious American and European meddling in its near-abroad. it also finds its roots in geography: As the Russian empire grew Eastwards, Southwards and Westwards from the 17th century onwards, the new territories were assimilated, each time pushing the borders further and further away from the centre of gravity of the empire. That newly conquered land provided Moscow with a geographical buffer, land to trade against time in case of a foreign invasion. This buffer reached its apogee after WWII with the Soviet occupation of Eastern Europe and the subsequent creation of the Warsaw Pact in 1955. In Eastern Europe. this buffer, extending all the way to Germany and including some geographical choke points thanks to the Alpine and Carpathian mountain ranges. Following the fall of the Soviet Union and the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact, Moscow witnessed the buffer zone between Russia and NATO melt away as the North Atlantic Organisation slowly but surely expanded Eastwards toward the Russian borders. Up until 2014, Russia only had two countries left acting as a buffer zone between its borders and NATO member states: Belarus and Ukraine. In the mind of Russian civilian and military planners, those two countries cannot fall into Western orbit: In the case of Ukraine, the Russian Ukrainian border is at some point less than 450km from Moscow. From Ukraine, looking North or East, the North European plain extends all the way to the Urals. There isn’t a single geographical feature where one could anchor a defensive line, not a single choke point. NATO troops in Ukraine or Crimea would mean a naked, indefensible Russia. Russia’s main agricultural lands are situated along the Ukrainian border. Russia’s main populated centres are all West of the Urals. A NATO push from Ukraine into Russia or NATO landings on the shores of the Black Sea would put all that region at risk. For Russia, this geographical position is a curse: A hypothetical NATO invasion of Russia would see North Atlantic troops follow the exact same roads and thrusts that led Napoleon in Moscow and led the Wehrmacht a stone’s throw away from its gates. Finally, there is no denying that the Ukrainian question goes way beyond the rational in Moscow: From the Russian point of view, Ukraine and Russia are sibblings. Ukraine is the cradle of the Kievan Rus civilisation. Ukraine is where the Russian language developed. where the Russian orthodox identity was born. Two countries, but a common past and a common cultural heritage. Ukraine is an emotional subject for many Russians.

The Russian New Generation Warfare has been inspired by the events of the 2008 Russo-Georgian war and by the eastwards expansion of NATO, all the way into Russia’s near-abroad and in some cases, all the way to the Russian border. Russia’s Hybrid Warfare was born of a blend of NATO expansion, perceived Western hostility and Russian paranoia. It is very obvious in Russian minds that Russia cannot compete against the West in yet another arms race. Hence the need for an asymmetric or hybrid solution. Russia’s strategy in Ukraine is the same as in Georgia: Carve a buffer zone in friendly territory (friendly/sympathetic population) in order to create a territorial dispute with the concerned country and impede said accession to the EU or NATO. There is no need to invade the whole country, be it Ukraine of Georgia, to reach that goal. Russia isn’t looking at conquering more land for the sole purpose of acquiring more land. Pushing further West into Ukraine would be counterproductive as it would mean occupying land populated by a hostile population… Preventing the return of the Donbass and Crimea to Ukraine in itself is a Russian victory in the eyes of its military leadership. As of today, 7.2 percent of Ukraine’s territory, including Crimea, is under Russian control. An area larger than the US state of Connecticut. Enough to create a buffer zone and enough to create economic hardship for Ukraine.

What does Russian Hybrid Warfare mean for the West? At the civilian / diplomatic level, it means an era of uncertainty: Russia’s asymmetric/undercover activities make it a partner difficult to read and predict. It also makes Russia’s near-abroad a more volatile area where a sudden Russian military surge, official or under the cover of a popular revolt, might be just months, weeks, hours away, without much in the way of warnings. For current NATO forces, forged in the fires of counterinsurgency operations for the past 20 years, a military clash with Russian forces near the Russian border would be a foreign and bloody experience: In the words of Amos C. Fox (US Army) “Many of the battles that embody these characteristics are unheard of in the U.S. Army. Battles such as Ilovaisk, Donetsk Airport, Luhansk Airport, Mariupol, Sloviansk, Debaltseve and others absorbed conventional combat unseen in quite some time. The contemporary, conventional Russian approach to warfare is important to understand because so few within the U.S. Army, especially at the brigade-combat-team level and below, are familiar with such forms and methods of combat”.

Избранные свежие новости мира часов – трендовые новинки легендарных часовых компаний.

Абсолютно все коллекции хронографов от дешевых до экстра люксовых.

https://bitwatch.ru/

Абсолютно все актуальные новости часового искусства – актуальные модели известных часовых брендов.

Точно все варианты хронографов от дешевых до супер премиальных.

https://bitwatch.ru/