Historical context: Struggle of Far East empires.

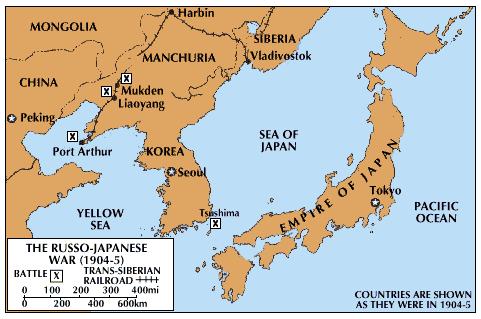

Tsushima: history’s most decisive battleship engagement. In the start of the 20th century, a new empire was rising upon Asia, one that intended to unify the Far East under its dominion, gaining therefore access to vast amounts of resources necessary for a growing industry. That was the Empire of Japan. Contrastingly, Russia, a much older empire, had her eyes upon Manchuria, from where her imperial interests could be extended to the Pacific.

By February 1904, without a formal declaration of war, the Japanese battle fleet launched a surprise attack on the Russian Far East Squadron docked at Port Arthur, thus initiating the Russo-Japanese war. For Japan, an island nation, to maintain a military campaign in Manchuria, it was imperative to keep control of the seas, as any communication with the armies in the continent had to be done by water, therefore the first target to be taken out was the Russian Navy.

Although inconclusive at first, the attack had the effect of trapping the Russian First Pacific Squadron in port, where it remained relatively safe under protection of shore batteries, but unable to deny the seas to Japan, allowing Japanese armies to be landed on Manchuria. After a succession of engagements, which deserves an article all in itself, the Japanese managed to defeat the Russians at sea and disable the remaining fleet in harbour by the use of heavy mortars.

When it became clear to the Russians that the First Pacific Squadron could not break free from Port Arthur, a relief squadron, designated Second Pacific Squadron, was assembled from Russia’s northern and Baltic fleets, and sent on its way across the world under the command of admiral Z.P.Rozhestvensky to lift the siege of Port Arthur.

Technological context: The Pre-Dreadnought Battleship.

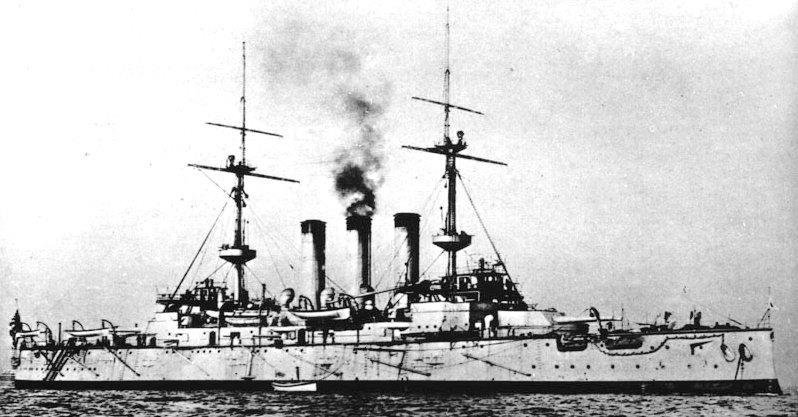

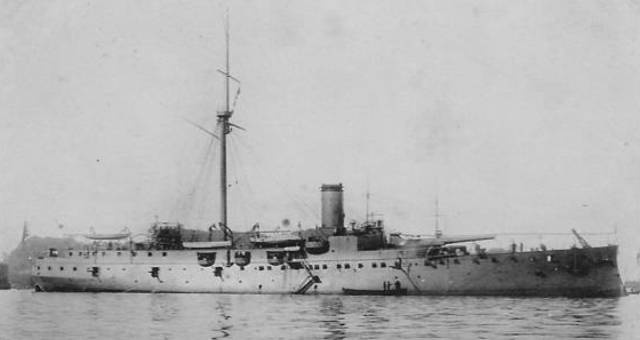

By the time of the Russo-Japanese war, naval powers relied upon the battleship as their main unit for fleet actions, being heavily armed but also well protected, able to maintain position in the battle line while under heavy fire. Cruisers, in charge of scouting ahead of the main body of the fleet and providing additional firepower where needed, supported these. Smaller but not irrelevant were the destroyers, armed with torpedoes, a novel yet immature weapon, which also had the function of carrying on liaison duties between capital ships during battle.

The main armament of the battleships at the time usually consisted of four 10 to12 inch guns mounted on twin turrets fore and aft, but due to the inadequacy of contemporary fire control and aiming systems those rarely scored hits on anything that was moving, the largest amount of damage being dealt by the secondary battery of the ships. Secondary guns were commonly of 6 inches in calibre, placed in casemates on the sides of the ship, and were able to make up for their inaccuracy by the means of sheer volume of fire, although single hits from these weapons rarely caused serious damage. Lastly came the smaller anti-torpedo boat batteries, composed of 12 pound (76mm) quick-firers, although smaller calibres were not unusual, and had the function of keeping torpedo boats away from the ship reducing dramatically the threat posed by early torpedoes.

At that time, most navies, Russian included, fired their guns with the roll of the ship, limiting the rate of fire, as the gunner had to wait for the ship to roll, bringing the target into bear, to fire his weapon. In 1899 however, a new method of gunnery was developed by the British, ‘Continuous Aim’, that consisted of keeping the smaller guns of the ship on target during the entire roll of the vessel with the aid of telescopic sights. The technique had shown astounding success in trials, improving the hitting rate of cruisers where that was tried out by 600 per cent, that’s it, a six with two zeroes after it. As the adoption of this method of gunnery was quite training intensive, only two navies in the world had adopted it by 1904, the Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy, and the difference would be felt later in battle.

The gunnery engagements were held in ranges no longer than 6000 yards (approximately 5400 meters), as this was as far as the weaponry of the ships could fire with any hope of hitting a target, for most of the duration of the engagement at Tsushima however, the battle lines were at closer ranges.

Torpedoes of the time were of reduced range and speed, reaching 3 kilometres at maximum range but doing only 15 knots, while increased speeds reduced the range of the weapons. Altogether hits could only be realistically expected against crippled ships unable to manoeuvre away from the weapons.

Order of Battle:

The Russian Fleet:

The Second Pacific Squadron consisted of the main fighting strength of the Russian Baltic Fleet, and as the Black Sea Fleet was contained by treaty, that was all the strength available at that point. As it became more and more clear that the possibility of joining up with the First Pacific Squadron was becoming less likely, a Third Pacific Squadron was assembled from old obsolete ships and, against the will of admiral Rozhestvensky, sent as reinforcement to the Second.

Second Pacific Squadron:

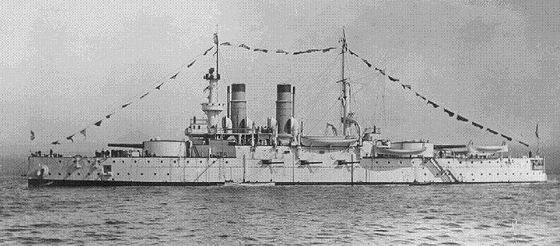

The four Borodino class battleships, Borodino, Imperator Aleksander III, Orel and Kniaz Suvorov, formed the fighting core of the squadron. Very modern vessels at the time, the last of them commissioned in 1904, they had an armament composed of four 12 inch guns in twin turrets fore and aft, twelve 6 inch guns in twin turrets three on each beam and ten 3 inch guns for torpedo boat defense on each beam, although too low for comfortable operation in high seas. Designed to displace 13500 tons, all of them were overweight by several thousand tons, which impacted negatively on their stability and speed, which was normally less than the maximum 17.5 knots, and also made it so that when fully loaded the entirety of their latest Krupp cemented armour was submerged and failing to protect the waterline. Their tumblehome hull design of French origin gave them very little reserve buoyancy and made them quite unstable upon flooding. Not to be discarded is also the fact that in such new ships most of the crew were not yet fully trained and proficient in the operation of the ship’s systems.

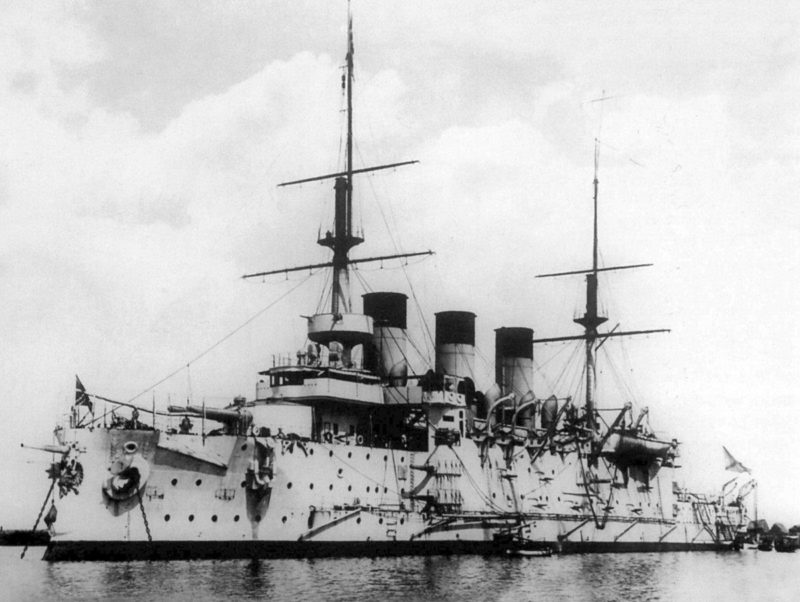

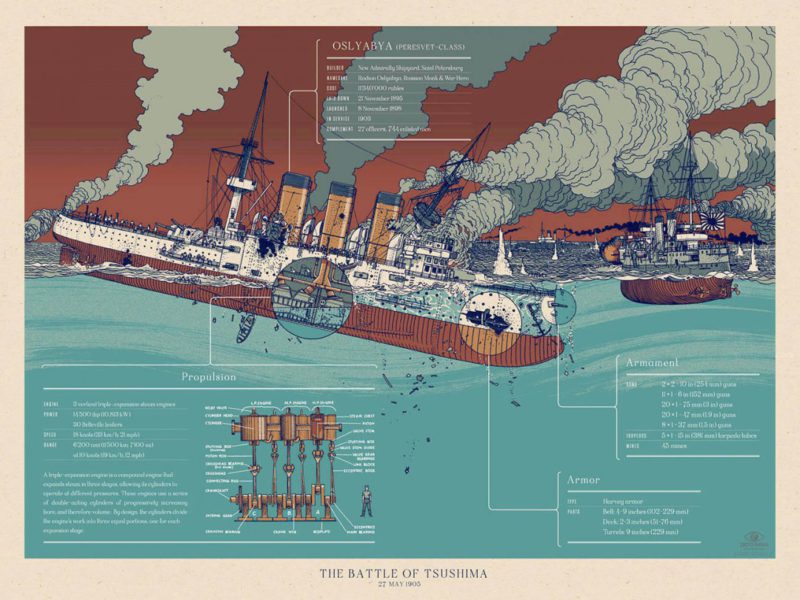

Comissioned in 1901, Osliabia was a 12683 ton battleship of a different design that emphasized higher volumes of fire, she was thus armed with four 10 inch guns in twin turrets fore and aft and eleven 6 inchers, five on each beam and one as a bow chaser. Anti torpedo-boat armament was the usual twenty 3 inchers. She maxed at 18 knots and when fully loaded also had her armour belt fully submerged, a flaw common to Russian designs.

Here the modern capital ships end, the rest of the squadron being composed of an earlier and obsolete generation of ships.

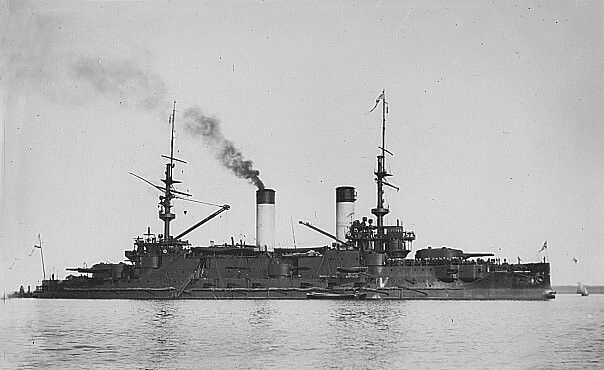

Sissoi Veliki, a 10400 ton battleship commissioned in 1896, she was armed with four 12 inchers in twin turrets but suffered from a weak secondary battery of only three 6 inchers on each beam, anti torpedo-boat armament was of twelve 3pdr (47mm) guns. She had a maximum speed of 15.7 knots at the expense of high coal consumption.

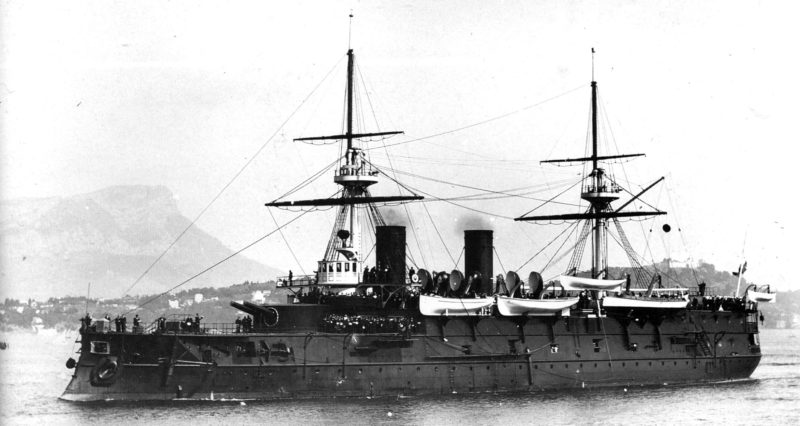

Navarin was a 10200 ton battleship commissioned in 1896 but even then considered to be obsolete, she had the same fashion of 12 inch gun arrangement of the above, although with less powerful 12 inchers, and four 6 inchers on each beam. eight 3pdr guns comprised the torpedo boat protection, and the ship was capable of steaming at 15 knots.

Admiral Nakhimov was closer to the definition of an armoured cruiser then that of a battleship, displacing 8500 tons she was completed in 1888. Her armament was of four 8 inchers in twin turrets fore and aft and aft, and five 6 inchers on each beam, but in unprotected batteries. Her top speed was of 14 knots and her armour inadequate at best.

The Third Pacific Squadron, under Admiral Nebogatov, was entirely composed of obsolete ships and Admiral Rozhestvensky had indeed considered them more of a hindrance to his fleet than anything else, referring to them as the “self-sinkers”.

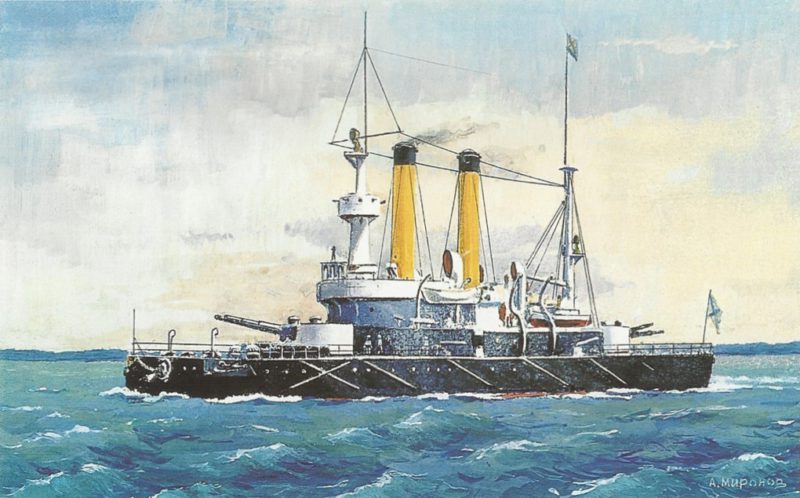

Imperator Nikolai I, Nebogatov’s flagship, was a 9672 ton battleship completed in 1892 but modernized in 1898. Armed with one twin 12 inch gun turret forward and a battery of two 9 inch guns an four 6 inchers on each beam. She mounted sixteen 3pdrs and steamed at 15 knots.

Lastly came the three coastal defence ironclads Admiral Ushakov, Admiral Seniavin and General Admiral Graf Apraksin, small vessels at 5000 tons they were armed with four 10 inch guns in twin turrets fore and aft and four 4.7 inch guns. Their maximum speed was about 15 knots however their design had not had high seas operations in mind.

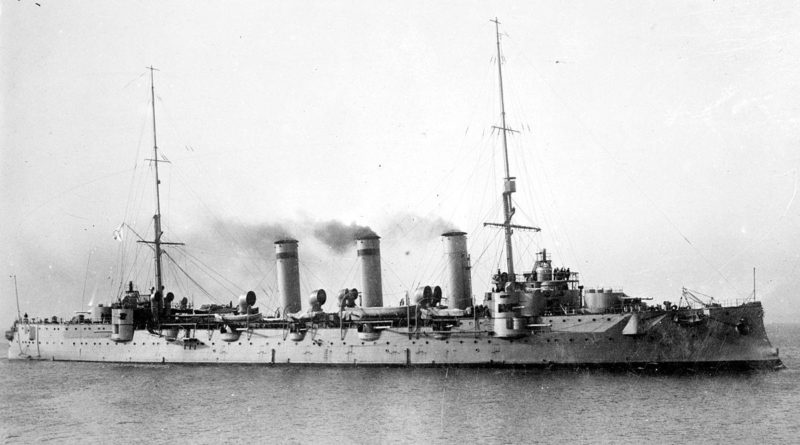

The support vessels in the Russian fleet were a mix of three modern cruisers capable of more than 19 knots, Svietlana, Oleg and Aurora, two old protected cruisers, Dimitri Donskoi and Vladimir Monomakh, too slow to be effective at 15 knots, two fast scout cruisers deployed with the destroyers, of which there were two divisions of four ships each, and 5 armed merchant ships. Not a very formidable fighting force by any extent of the definition.

The Japanese Fleet:

In contrast to the largely obsolete Russian Squadron, Japanese Admiral Togo Heihachiro had a fleet comprised largely of modern ships of good design crewed by battle hardened sailors. They had had time to repair battle damage from the Yellow Sea in Japan and were ready for action when the Russian fleet arrived. The lack of battleships was compensated for with the addition of armoured cruisers on the battle line.

The first division under Admiral Togo consisted of all 4 of the modern battleships plus two armoured cruisers.

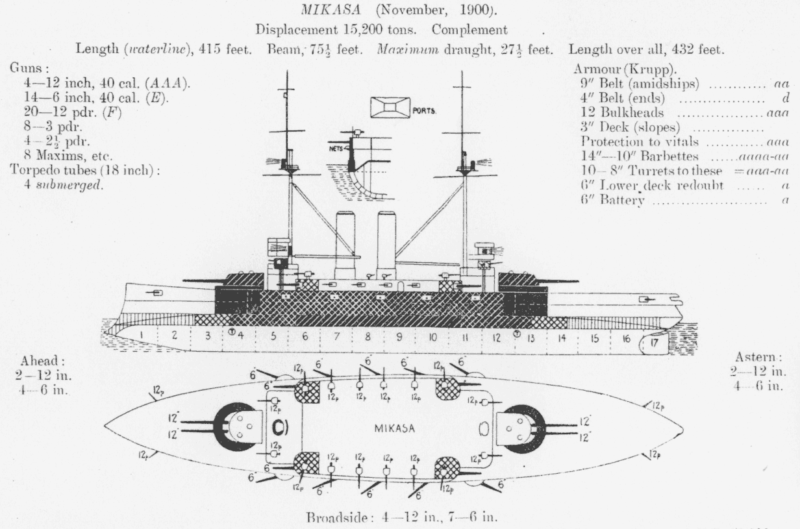

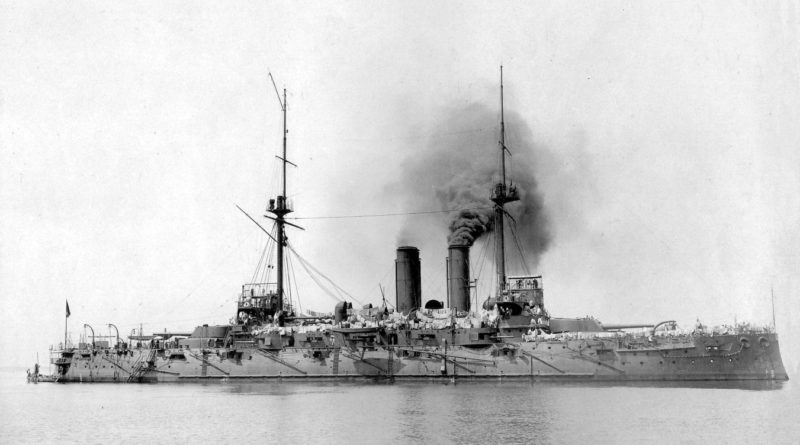

Admiral Togo’s flagship was the 15600 ton Mikasa, launched in Britain in 1900 built to the latest British battleship designs. She was armed with four 12 inch guns in twin turrets fore and aft and fourteen 6 inchers, seven on each beam. Torpedo boat protection was provided by twenty 12pdrs and the latest Krupp cemented armour was employed in the belt and barbettes. The ship was capable of 18 knots, and was considered to be one of the best protected and effective of her time.

Fuji was somewhat older launched in 1897. Displacing 12500 tons she had an armament of four 12 inch guns in the usual fore and aft twin turret arrangement, however the guns could only be loaded with the turrets trained fore and aft, limiting the rate of fire. Ten 6 inchers comprised the secondary armament and the ship had sixteen 12pdrs. Maximum speed was 18 knots.

Asahi was a 15200 tons battleship, completed in 1900 she had an armament of four 12 inch guns and fourteen 6 inchers as well as twenty 12pdrs, her armour was not as modern as Mikasa’s however a good internal subdivision had allowed her to survive hitting a Russian mine earlier in the war. Her maximum speed was 18 knots.

The last battleship was Shikishima, a 14850 ton ship launched in 1900. Her armament was comprised of the usual four 12 inchers in twin turrets and fourteen 6 inchers, and she was capable of steaming at 18 knots.

As we look at the Japanese battleships it becomes clear that a formation of such ships would have a much higher speed then that of the Russian formation limited to less than 15 knots, an advantage not to be taken lightly as it would allow the Japanese to keep the initiative and control the engagement throughout the duration of the battle.

As we consider pre-dreadnought gunnery and the importance of the 6 inch gun, we must not forget that the large armoured cruiser was a capital ship as powerful as the battleship although less armoured, and the Japanese had 8 of them. Their armament was arguably more effective in battle then that of the battleships, as continuous aim could be employed in the 8 inch guns, rendering them better at hitting long range targets than the 10 and 12 inchers of battleships.

Kasuga and Nisshin were 7700 ton vessels built in Italy. Armed with one 10 inch gun forward (or, in the case of Nisshin a twin 8 inch) and a twin 8 inch turret aft, the secondary battery had fourteen 6 inchers. The vessels were capable of 20 knots.

The remaining armoured cruisers formed the second division under Vice-Admiral Kamimura.

Idzumo and Iwate displaced 9750 tons, completed in 1901. Armed with four 8 inchers in twin turrets and fourteen 6 inchers they were every bit as effective in battle as a battleship, and faster at 20.75 knots.

Asama and Tokiwa were of the same pattern, built in England and launched in 1899. Their maximum speed was restricted to 19 knots for safety reasons.

Adzuma displaced 9370 tons. Completed in France in 1900 she was similar to the above mentioned ships but short two 6 inch guns. Equally armed was the 9646 ton Yakumo, built in Germany in the same year.

Support ships were comprised of 8 cruisers, most of them capable of more than 20 knots, five divisions of torpedo-boat destroyers and some additional dispatch vessels.

Also deployed were older obsolete vessels in support duties, such as the third squadron under command of Vice-Admiral Kataoka, that being three Matsushima class cruisers, an old ship displacing 4217 tons and armed with one 12.7 inch gun and eleven 4.7 inchers, the former Chinese ironclad Chin Yen and 6 old cruisers of 1890s vintage. Also deployed were 27 small torpedo boats.

Lastly the Auxiliary Squadron composed of 3 torpedo boats and 7 auxiliary merchant cruisers which Togo used for scouting.

The Engagement:

Encounter:

From the moment Rozhestvensky realized that the First Pacific Squadron besieged at Port Arthur was doomed and no hopes remained of lifting the siege, his intentions were to make for Vladivostok without engaging the main body of the Japanese fleet, although destroying smaller isolated units if the situation presented itself in order to satisfy political purposes.

The admiral was aware of the poor shape of his fleet, not adequately drilled in gunnery nor manoeuvre, and limited in its speed and manoeuvrability by the likes of Admiral Nakhimov and other obsolete vessels. Any decisive battle would at that point favour the Japanese, and it was in Rozhestvensky’s best interest to avoid it. By reaching Vladivostok he would be able to keep his fleet safe and significant as a fighting force, contesting the Japanese control of the ocean and waiting for a better moment to attack.

In order to induce Togo to divide his fleet, Rozhestvensky sent a pair of AMCs to the coast of Japan and another pair to Shanghai, the main body of the Russian fleet would steam to Vladivostok trough the Strait of Tsushima sinking whatever they came upon without breaking formation, or so went the plan anyway.

The Russian fleet was formed in three battleship divisions of four ships each, the first being the Borodinos in line in the head of a column, followed by Osliabia, Sissoi Veliki, Navarin and Admiral Nakhimov forming the second division, Parallel to them was another column formed by the self-sinkers of the third pacific squadron forming the third division followed by the first cruiser division. The columns were screened by the fast cruisers and two destroyer divisions, which would however be attached to the transport ships in the case of a battle, and all the formation was preceded by AMCs in a scouting role.

Admiral Togo, knowing his ships to be faster and his formation more maneuverable than the Russian one, intended his first squadron to cross the Russian’s T and his second squadron to attack from a different direction concentrating his firepower on a specific portion of the enemy fleet in order to destroy it as quickly as possible, and , knowing that the Tsushima strait was the most likely way for Rozhestvensky to steam towards Vladivostok, he laid a screen of cruisers and AMCs in order to detect the Russian fleet. For the Japanese it was essential to win a decisive victory, as the island nation was hard pressed to sustain the war and desperately needed to bring the enemy to the negotiating table in order to seek favourable terms.

In the 27th of May, at 04:45 the AMC Shinano Maru spotted the Russian formation and radioed its position to the Japanese fleet and by 13:39 Togo had visual contact with the Russian fleet.

The ‘Z’ flag then flew from Mikasa’s main mast, its meaning being “The Empire’s fate depends on the result of this battle, let every man do his utmost duty.”

The Russians had formed a battle line with the third division forming behind the first and second and the cruisers and transports forming to starboard with the destroyers between them.

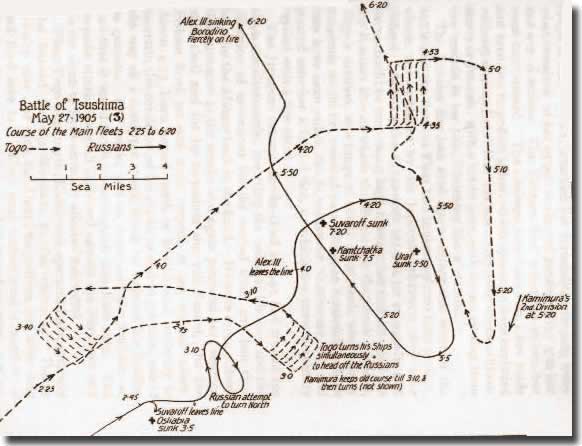

Day Action:

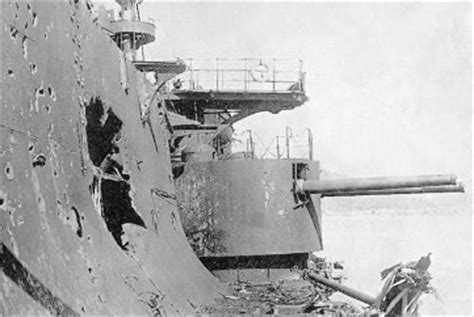

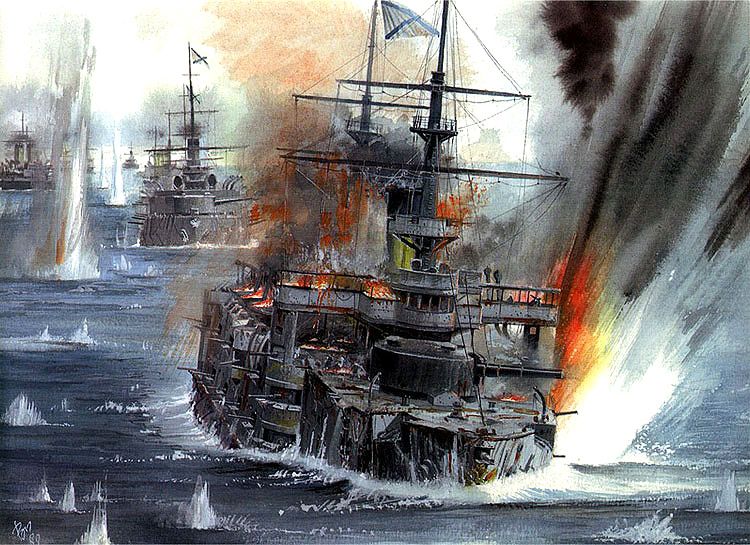

The first shots of the battle were fired by the Russians as the Japanese executed a turn to port in order to get in a better position to attack the Russian vanguard, but few hits were made and the Russian shells were quite ineffective. Then the Japanese opened fire at about 6000 yards, concentrating their fire on Osliabia and Suvorov, to devastating effects. The 6 inch guns of the Japanese using continuous aim and firing high explosive projectiles loaded with Shimose, an especially powerful explosive for the time, had the effect of setting fire to anything made of wood and sweeping the decks with splinters, but occasional 8 inch and 12 inch hits were reported.

The fleets kept on parallel courses with the Russians manoeuvring in order to avoid having their T crossed and the fire being exchanged at a range of 5500 yards, with the Russian return fire being seriously affected by the effects of the high explosive and fires on their ships.

By 14:40 the Japanese closed in and managed to land two more 12 inch hits on Osliabia, which turned to starboard, stopped and developed a bad list to port as the captain flooded the port magazines in a failed attempt to balance the flooding to starboard, sinking about 40 minutes later. and the survivors were picked up by destroyers. In quick succession the flagship Suvorov suffered a destroyed main bridge and jammed steering and turned to starboard falling out of the line.

The fleets then resumed the exange of fire at 3500 yards, with the advantage going to the Japanese due to their more effective shells. The Japanese second division then crossed the Russian T and kept the highly effective fire on the leading enemy ships. The confusing manoeuvers made by the Russian line as it attempted to follow the damaged Suvorov and then reverting to the original course led into confusion in the Japanese line, and at about 15:10 the fleets parted for a brief period of time, with Togo fearing an attack on his rear by an unseen portion of the Russian fleet, at 15:49 he had his line reformed at the previously mentioned order and steaming back towards the Russian fleet. By 15:45 another hit on the conning tower of the Suvorov wounded Admiral Rozhestvensky on the head and put him out of combat unconscious.

The fleets met again at 16:00, with the Russians being forced to change course to avoid getting their T crossed, which led the Suvorov, which had been the main target of the second Japanese division for a considerable amount of time, to become completely exposed to the first division, which focused its fire on the stricken Russian flagship, which allowed the Russian fleet to open distance into the mist.

As Togo turned his ships to port in order to protect his rear against a Russian manoeuvre he actually broke contact with the Russian fleet, and as he turned to port at 17:00 Japanese destroyers found the Suvorov still making 10 knots and managed to hit her with one torpedo, causing further damage. Any further attack on the Suvorov was however sent off by the arrival of the Russian fleet, which had made a turn to starboard and come back on a northerly course to rescue the Admiral.

By 17:50 the Russians had managed to reform the line and transfer Admiral Rozhestvensky from the Suvorov to the destroyer Buini, command of the fleet being officially transferred to Admiral Nebogatov. The line now was led by Borodino and had the damaged Aleksander III out of it on a parallel course to starboard, astern to starboard were the transports and to port came the cruisers. Even though shots were still being fired at that point they were not very effective at 6500 yards.

By 18:50 Aleksander III fell out of line to port, turned over and sank together with 836 of her crew, leaving four survivors.

As the light was getting low, Togo ordered the Japanese formation to cease fire, and at 19:20 as Fuji fired her last salvo which was already loaded. She scored a 12 inch hit on the forward magazine of the Borodino, causing a massive explosion which led the ship to capsize and sink together with her compliment of 855 men, of which only one was saved.

As the Japanese torpedo boats were barring the way, the Russian fleet took a south-easterly course.

Meanwhile the Japanese third division under Kataoka, tasked with sinking the stragglers, occupied itself with the Suvorov, and managed to land several 12.6 inch hits and in the end 3 torpedoes fired at a range of about 300 yards, something which was only possible because most of the 3 inch guns had been disabled by the torrent of high explosive. The torpedoes managed to detonate a magazine and at 19:30 the Suvorov capsized and sank with all hands.

Night Action:

On this new phase of the battle Togo sent his torpedo boats to attack the Russian fleet, although the heavy seas made it really hard for them to attack effectively. Hits were scored on two of the old armoured cruisers, which would sink later. Also hit was Navarin, although she was sitting still in the water from previous battle damage, they were however not the cause of its sinking, as that happened the following morning as the battleship had gotten underway again and hit two mines laid ahead of her by the destroyers. The battleship Sissoi Veliki was also hit by one torpedo on the aft, and started to flood, surrendering the following morning and sinking at about 09:30.

Russian Surrender:

By 10:30 the following morning the Japanese fleet opened fire at a range of 7500 yards against what was left of the Russian line, and as there was no hope of responding in any effective way with the surviving ships, as their artillery was old and obsolete, the only modern vessel remaining being Orel, which was too damaged to be effective. At that point the entire Japanese fleet was making a ring around the remains of the Russian formation, and no capital ship was missing. Upon the sight all hopes were lost for the Russian fleet and Admiral Nebogatov ordered the fleet to surrender, in spite of a high chance of being shot for issuing such an order.

Admiral Rozhestvensky was captured later this day as the destroyer Byedovi surrendered to pursuing units.

The only significant body of Russian ships not sunk or captured was composed of the cruisers Aurora, Oleg and Femtchug, which escaped southwards and were interned at Manila by the Americans.

Important Conclusions:

Firstly we can observe how significant was the Japanese advantage in speed over the Russians, whose line was often steaming at speeds as low as 9 knots during the battle. This advantage allowed the Japanese to decide the range and angle of engagement, and always have the Russians on the defensive desperately attempting to avoid having their T crossed. It was also an advantage as the fleeing Russian formation was unable to break contact in the end, with the Japanese fleet managing to surround them.

Another advantage held by the Japanese was their superior gunnery, as the better drilled gun crews employing continuous aim managed a higher rate of fire and superior accuracy then that of their Russian counterparts. Also relevant was the ammunition employed, as Togo’s ships made constant use of small calibre high explosive fired at the superstructure and upper decks of enemy ships at ranges where armour piercing would have been ineffective, and managed to set fires and destroy exposed guns and rangefinders, wrecking the Russian capacity to lay accurate fire and in many cases even to hold formation, as well as disrupting the action of damage control parties.

The effects of the Japanese shelling can be described by the words of Captain 2nd rank Vladimir Semenoff, on board the Suvorov: “It seemed as if these were mines, not shells, which were striking the ship’s side and falling on the deck. They burst as soon as they touched anything — the moment they encountered the least impediment in their flight. Handrails, funnel guys, topping lifts of the boats’ derricks, were quite sufficient to cause a thoroughly efficient burst. The steel plates and superstructure on the upper deck were torn to pieces, and the splinters caused many casualties. Iron ladders were crumpled up into rings, and guns were literally hurled from their mountings.

Such havoc would never be caused by the simple impact of a shell, still less by that of its splinters. It could only be caused by the force of the explosion. The Japanese had apparently succeeded in realizing what the Americans had endeavored to attain in inventing their “Vesuvium.”

In addition to this, there was the unusual high temperature and liquid flame of the explosion, which seemed to spread over everything. I actually watched a steel plate catch fire from a burst. Of course, the steel did not I burn, but the paint on it did. Such almost non – combustible materials as hammocks, and rows of boxes, drenched with water, flared up in a moment. At times it was impossible to see anything with glasses, owing to everything being so distorted with the quivering, heated air. “

The Russian return fire was mainly composed of armour piercing shells aimed at the hull of enemy ships, and quite inaccurate at that, causing very limited amounts of damage to the Japanese ships, attesting to their ineffectiveness is the fact that Admiral Togo commanded the battle from the open bridge of Mikasa, without as much as a roof for cover, and did not retire to the armoured battle bridge.

Also to be observed is the scarcity of 12 inch hits on either side, but the devastating effect of such hits as the one which sunk Borodino for example or the one that caused flooding on Osliabia. It must be noted that the Russians possessed 42 guns of 10 inches or more against 17 on the Japanese line albeit with approximately twice the rate of fire, and yet the latter held the edge in every single exange of fire in the battle.

It must not go unnoticed that out of 87 torpedoes fired in the battle only 8 hits were scored, and most of them on crippled ships such as the Suvorov and Navarin, and that only the old cruiser Vladimir Monomakh sunk primarily due to torpedo damage, as the other ships hit by torpedoes already suffered from countless other hits. That emphasizes the immaturity of the early torpedo as an effective ship sinking weapon, as it was better suited for finishing off crippled ships then being fired at a vessel moving at full steam which they stood little chance of hitting.

Lastly attention must be given to the deficiencies of the design of the Russian battleships of the Borodino class, as they quickly became unstable upon flooding having a tendency to capsize and sink. That happens mainly due to two reasons: Firstly the tumblehome design of their hull, which is normally stable enough but lacks reserve buoyancy and tends to loose righting moment the lower it sits in the water in a much more serious way then a straight sided hull. Secondly, the ships were already overweight from the start, something which aggravated the deficiencies of the hull design.

Many of the blame for the defeat fell upon the shoulders of Admiral Rozhestvensky, who assumed full responsibility upon court martial when he returned to Russia, his death sentence was however commuted by the Tsar on grounds that he was unconscious for most of the duration of the battle. Admiral Nebogatov, who was in command during the majority of the battle faced the same court martial and spent some time imprisoned. Both men’s careers and reputations were ruined.

It would be however at least partially unfair to lay the blame on the admirals as the high command should have known better then to send a fleet comprised entirely of ships either obsolete or untested fresh out of shipyard on a desperate voyage halfway around the world with untrained crews to fight one of the best equipped and battle hardened naval fighting forces in the world, one which had already defeated a Russian fleet in battle.

Broader consequences:

On the words of Sir Julian Corbett the battle of Tsushima was “perhaps the most decisive and complete naval victory in history”, with 12 Russian capital ships sunk and four captured, 4830 men killed, 5907 taken prisoner and 1862 interned for the duration of the war against 3 torpedo boats (2 lost to Russian artillery and 1 sunk due to hard manoeuvers) and 117 men lost on the Japanese side.

The victory at Tsushima completed the utter annihilation of the Russian naval presence in the Far East and allowed Japan uncontested control of the seaways. The broader political consequences of that victory however were of even greater importance as the pressure for Russia to negotiate peace grew too strong to be ignored and allowed for an exhausted Japan to settle an agreement and end the war at the best possible moment, as any continuation of the land war would almost certainly favour Russia, who had managed to amass a large army in Manchuria and had it supplied via the Trans-Siberian railway. Without such a decisive victory the Russians would probably have turned the tide in land deprived the Empire of Japan of all crucial resources conquered in the war.

Sources:

“Grove, Eric. Big Fleet Actions. London: Arms and Armour Press, 1991”

“Forczyk, Robert. Russian battleship vs Japanese battleship. Oxford. Osprey Publishing Ltd, 2009”

For the complete extract of Capt. Semenoff’s notes visit the website: